Everyone dreams of living in Brooklyn at some point in their lives. If someone says this isn’t true, they’re lying. The brownstone brick, the tree lines streets, and the tin roofs of coffee shops evoke a sense of wonder.

“Hey Lady, move a little slower why don’t ya, it’s not like I have anywhere to be!”

The man in the Fresh Direct delivery truck turning from 5th Avenue onto Union Street is most likely my exact age. He’s a dark-haired beauty with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth, five o’clock shadow, white t-shirt, and a blue and white trucker hat with red letters across the front that spell out “I PEE IN POOLS”. If I wasn’t holding my three-year-old son’s hand, balancing a tote bag on one shoulder, and trudging along a heavy sack of groceries; if my tits didn’t look like sandbags, if this were twenty-five years ago, I might have smiled. Maybe. We might have exchanged numbers, and I would have absolutely bought a matching hat in pink. But because I’m tired, and middle-aged, and a mother, and mostly because I’m from Brooklyn, I shift the shopping bag from my hand to my wrist so that I can flag my middle finger in this guy’s face.

“Sit on it and rotate, asshole,” I yell, to which he responds by blowing me a kiss, to which I respond with the typical, smirking, “in your dreams, buddy.”

It doesn’t matter that some of my hair is gray. Who cares that the brown stain on my sweatshirt from a greasy falafel ball looks like a dirty heart. It doesn’t even really make a difference that my son, trailing alongside me, has his finger all the way inside of his nose almost down to the ashy knuckle. In Brooklyn, I am beautiful, aging backwards like my borough. The man in the Fresh Direct truck is a bonus. He’s my daily reminder that no matter what happens, “I still got it,” even if the “it” that I “got” is a shitty attitude and a lot of confidence.

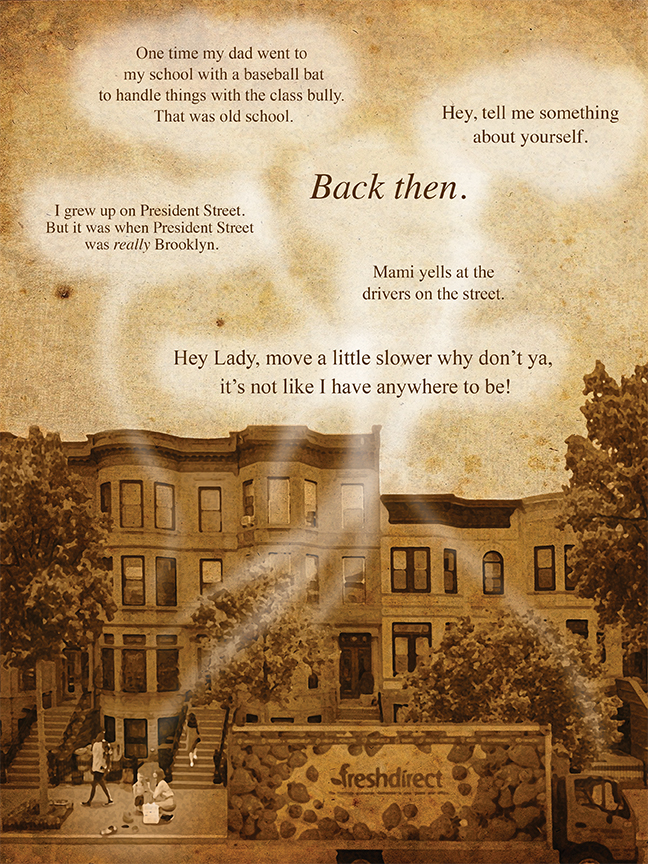

Brooklyn exists in a cloud of nostalgia. It is the borough of “before.” It is the county of sentimentality, wistfulness, and the memory of a yesterday we aren’t even sure existed in the first place. Everyone wants a piece. Everyone dreams of living in Brooklyn at some point in their lives. If someone says this isn’t true, they’re lying. The brownstone brick, the tree-lined streets, and the tin roofs of coffee shops evoke a sense of wonder. People who grew up here, or even long-time residents who have made it to Brooklynite status, shamelessly recount tales of “the old days.” The old days are visions of a time when things in Brooklyn were real, original, creative, authentic. In these tales told by Brooklyn elders, life always appear to be better or simpler. The stories often begin with a setting or an unlucky situation.

“I grew up on President Street. But it was when President Street was really Brooklyn.” Another popular opener is, “One time my dad went to my school with a baseball bat to handle things with the class bully. That was old school. That’s how we dealt with things back then.” Back then. The story unfolds as if there is a lease on time and that part of history never moved past the father’s grip on the bat. In the myths and legends of Brooklyn, store owners know every child’s name on the block, bad guys get dealt with by tough guys, and parents are rarely around, entrusting their children to the peeping eyes of the neighborhood grandmothers who lean out of windows in floral nightgowns and see all. In this way Brooklyn and its people never grow old, even if they are old. In fact, they don’t grow old even if they’re dead. Brooklyn is fiction; the Never Neverland of New York.

My own story of Brooklyn is broadcast in a similar fashion. When approached by a stranger with the question “where are you from?” my answer is always, “I’m from Brooklyn.” Most of the time, the question that follows is, “no, but originally.” I think the reason for this is that nowadays I look like a midwestern Mom of three who has no clue where I left the keys to my apartment even though they’re in the tie-dye fanny pack attached to my waist. This makes my nostalgic Brooklyn tale even more crucial. “What? What do you mean? I’m from Brooklyn, and my father’s from Brooklyn, and my grandparents came here when they were six! And everyone in my family watched the Brooklyn Dodger games from their roof! Oh, and Coney Island, we went to Coney all the time, and ate hot dogs, and we were happy!” As I scream and rant about the schools I attended, how my mother would take me to the Brooklyn Museum every weekend, how my Dad’s best friend lived on fifteenth off of Prospect Park and got stabbed ten times on his way home one day, I wonder if I am telling the stories to prove something to the listener, or more so to prove something to myself.

As our own youth disappears, as the reality of the enormity of life shifts into clear view, the stories we tell ourselves, the narratives we save for others, becomes the history of a borough that never wanted to grow up. There are always two Brooklyns simultaneously existing for most of us. For example, when I flip off the Fresh Direct, Bruce Springsteen look-a-like driver, I also feel the past creep up my neck like a whisper from a stranger in a dark bar. “Hey,” the voice says, “tell me something about yourself.” The man in the truck, cigarette falling from full lips, tempts the me from another time. But the reality, the day-to-day is often bleak, and out of this daily bleakness is where the seed of beauty is planted. In a few hours I must pick my two daughters up from school. At five o’clock I have to make dinner. At eight o’clock everyone goes to bed after a bath, and then I get ready for the next day. School, lunch, walking to my Mom’s house to give her a shower because she’s just had hip surgery. More cooking, waiting for my husband’s day off so that I can do everyone’s laundry. Then the stories emerge, erupting out of me, the tales my children will tell to keep the heart of the neighborhood beating forward into tomorrow.

“Mami yells at the drivers on the street,” my seven-year-old has been known to tell her teachers at school. “She gets so mad and then she yells and then they wait for us to cross the street. Also, one time, Mami chased a delivery guy on a bike because he didn’t say excuse me.” Her teachers nod and smile, and at a parent-teacher conference they show me a picture she drew of me running after the cyclist. I laugh because the legends of the Brooklyn mother have already started circulating throughout the grade and on the classroom’s group chat. In Brooklyn, to become a legend, even if only in a small child’s Crayola depiction, is to age backwards, to be frozen in the time of someone else’s memory. To be a part of Brooklyn, to become its concrete, its brownstones, its front stoop chalk games, is to have stories told about you by someone else.

After all, life can be mundane at best, cruel at worst. As the Fresh Direct truck disappears into the distance of Union Street, the grocery bag I am holding rips open halfway down the block. A box of gluten free cookies, a large can of coconut water, an organic dark chocolate bar, three apples, and two ripe bananas roll out onto the sidewalk. “Shit,” I say staring at the pretentious mess in front of me. The spill has me asking myself what version of Brooklyn I am living in now. When historians look back at Brooklyn today, will a sepia photo of me screaming on a street corner holding my son’s hand appear? Will the coffee shops and restaurants have a fuzzy look to them in the textbooks people study?

“Oh man, that sucks,” a teenage boy says as he passes my mess.

“Yeah, don’t offer to help or anything,” I snap back while shoving the chocolate and coconut water in my tote bag, trying to untangle the ripped plastic shopping bag from the bananas.

“I’m in a rush, lady,” he puts his air pods in so that he doesn’t have to hear me when I answer.

But it doesn’t matter. I’m already fiction. I’m already aging backwards, a frozen photo still of a woman bending down to pick up her fallen groceries, on the epic, unending streets of Brooklyn.