By Julia DePinto

“Photographing strangers on the street is like having an epic novel read aloud to you, only it’s real. You’re connected. You’re involved. And you carry every piece of it with you from then on.”

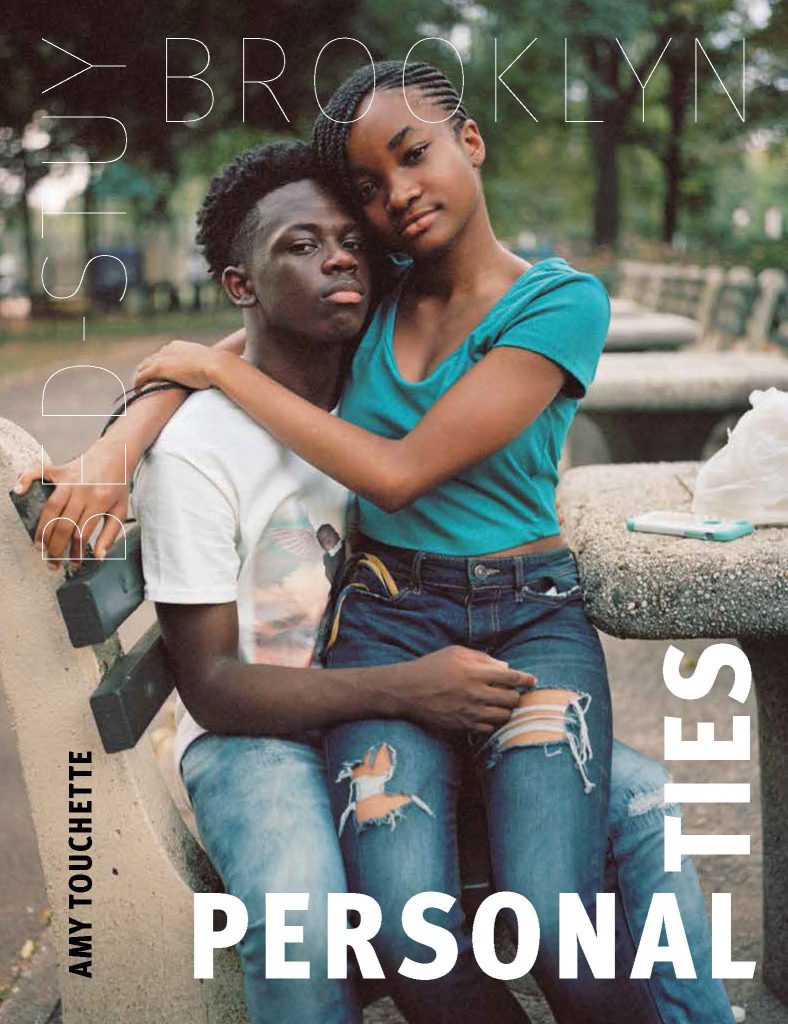

Amy Touchette, Personal Ties: Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn

Touchette adores New York City. The visceral energy and the frenetic vibrations; the architecture; the history; the diversity and blending of cultures— the city is a sea of inspiration for visual artists and storytellers to sink into. Touchette spends the late afternoons of warm summer days canvassing the city’s streets and searching for captivating characters. Her photography practice explores themes of social connectedness by celebrating New Yorkers in their communities and within their social groups. An antiquated Rolleiflex film camera makes her intentions explicit. Young people gathered in units, families sitting on stoops, grannies pushing carts of groceries, and teenage girls flaunting their individuality, are among the subjects of her pictures. Touchette provides her subjects with the space to present themselves in their most authentic form, highlighting the features that make them emboldened and unique.

“One of the greatest things about New York is that you can be a misfit,” Touchette told me, in a phone interview. “Misfits belong here.”

Touchette moved to New York City in 1997, after completing a Master’s degree in Literature and living in San Francisco and DC. She worked as a managing editor in the publishing industry and painted large-scale compositions of jazz musicians in her kitchen. She was steadily climbing the ladder of corporate America when the unthinkable events of September 11 transpired. At the time, Touchette was living on Bleecker Street in the West Village, only a few train stops from the Twin Towers. Traffic was cut off from her neighborhood and the stench of smoke and death was unavoidable. The landscape had been permanently altered.

“It looked like the end of the world had come,” said Touchette.

She described the horror of the terrorist attacks and the extraordinary loss that New Yorkers felt. Touchette’s younger brother had enlisted in the army one year before the attacks and was one of the first troops to deploy to Afghanistan.

“It was surreal. There were all these posters up that said ‘have you seen my mother’ or family member and it was awful because if you didn’t have a loved one missing you knew they were gone.”

Feelings of devastation brought on by the events of 9/11, coupled with feelings of loneliness and complacency in her career led Touchette to rethink her profession and life’s pursuits. She enjoyed oil painting, albeit a solitary art practice, but was searching for a greater purpose and desired human connection. The posters of missing persons were reminders of her mortality. Street photography, Touchette decided, easily lends itself to being an interactive medium. Making pictures of community members would ease the feelings of solitude and satisfy her anthropological curiosities about the human condition.

“It felt imperative to do what I was supposed to be doing— which was photographing my community,” said Touchette. “9/11 was such a tragic event any way you look at it but it yielded one of the best things that have ever happened to me in my life. It’s very incongruous and it has always confused me, but it is what happened.”

Touchette enrolled in photography courses at the International Center of Photography. She traded her corporate position for freelance writing opportunities that allowed for flexible scheduling. She worked enough hours to pay the rent but prioritized photography projects. The shifting landscape of the great metropolis and the recovery efforts of the 9/11 aftermath were secondary to Touchette’s conceptual interests. Her pictures, void of arrogance and lofty expectations, capture the interconnectedness of humanity— and advance brief but meaningful dialogue. Today, Touchette routinely takes two frames, providing little to no instruction. She allows her subjects to present their authentic selves, gaining much of their trust before documenting their mortality. These ephemeral moments of raw human exchange are invaluable to Touchette’s aesthetic.

Touchette moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn in 2005 and to Bedford-Stuyvesant in 2015.

(Amsterdam, 2021).

“Bed-Stuy is very vivid,” Touchette explained. “It’s interactive; it’s inclusive; it’s community-oriented. I got that feeling as soon as I arrived.”

Touchette documents the streets of her adopted community by engaging with Brooklyn natives and introducing both her analog camera and iPhone. The pictures tell the stories of her beloved community, echoing shared human experiences and collective desires. A small portion of Touchette’s film portraits of Bed-Stuy residents culminated into a recently published monograph, appropriately titled, “Personal Ties: Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn.” The book celebrates the relationships between families, friends, couples, and culture of the historically Black neighborhood.

The coronavirus pandemic presented Touchette with new technical and visual challenges. For one, state and city mandates required New Yorkers to stay inside and socially distance when outdoors; and two, strict mask mandates were enforced. Facial expressiveness is instrumental to the art of portrait photography. Touchette, however, embraced the challenges the pandemic presented. She photographed New Yorkers from safe distances in open-air spaces and incorporated the masks into her aesthetic. She found that Brighton Beach occupants were particularly welcoming.

Touchette is currently working on a series of candid street portraits taken with her smartphone. Unlike the collaborative pictures she makes with her film camera, these pictures are taken quickly, candidly, without express permission beforehand. The series, “Street Dailies” feature Touchette’s favorite NYC muses and are archived on Instagram. Touchette explained that the advent of digital photography and the rapidly developing technology of smart cameras and social media are essential to her art.

“It’s very liberating to photograph with a smartphone because I can capture moments that I can’t always get with my film camera. I really believe in the candid, documentary approach— I don’t always want to see the photographer’s heavy hand in the photo.”

Editor’s Note: I first spoke with Amy Touchette in early May, on a weekday when major news headlines were nuanced and predictable. The ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine and continued outrage among progressives over the leaked SCOTUS draft overturning Roe headlined the day’s top stories. Amy and I discussed her two-decades-long career of street photography— including thousands of pictures, numerous awards and exhibitions, a poker-sized deck of playing cards, and a recently published monograph. We also discussed the 9/11 terrorist attacks and how the event impacted her personal life and career trajectory. Two weeks later, as I was finishing this feature, the breaking news of the terrorist attack at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, TX began to circulate. Sad and angry at the things I alone can’t resolve, I stopped writing and began to consume as many of the grim details as I could stomach. When the photos of the young victims began to surface, I was suddenly reminded of our conversation and the visceral weight a picture can carry. Photographs are records of human mortality. Beneath the surfaces of the images of the children, lie the complexities of our existence.

Amy’s pictures are evocative of the moments that shape our lives— and forever remind us of the sanctity of being alive. When I look back through Amy’s pictures, I can appreciate the good in humanity. The bold personalities she captures, the intimate moments between families and friends, and the personal ties within community. They remind me to never give up on humanity.