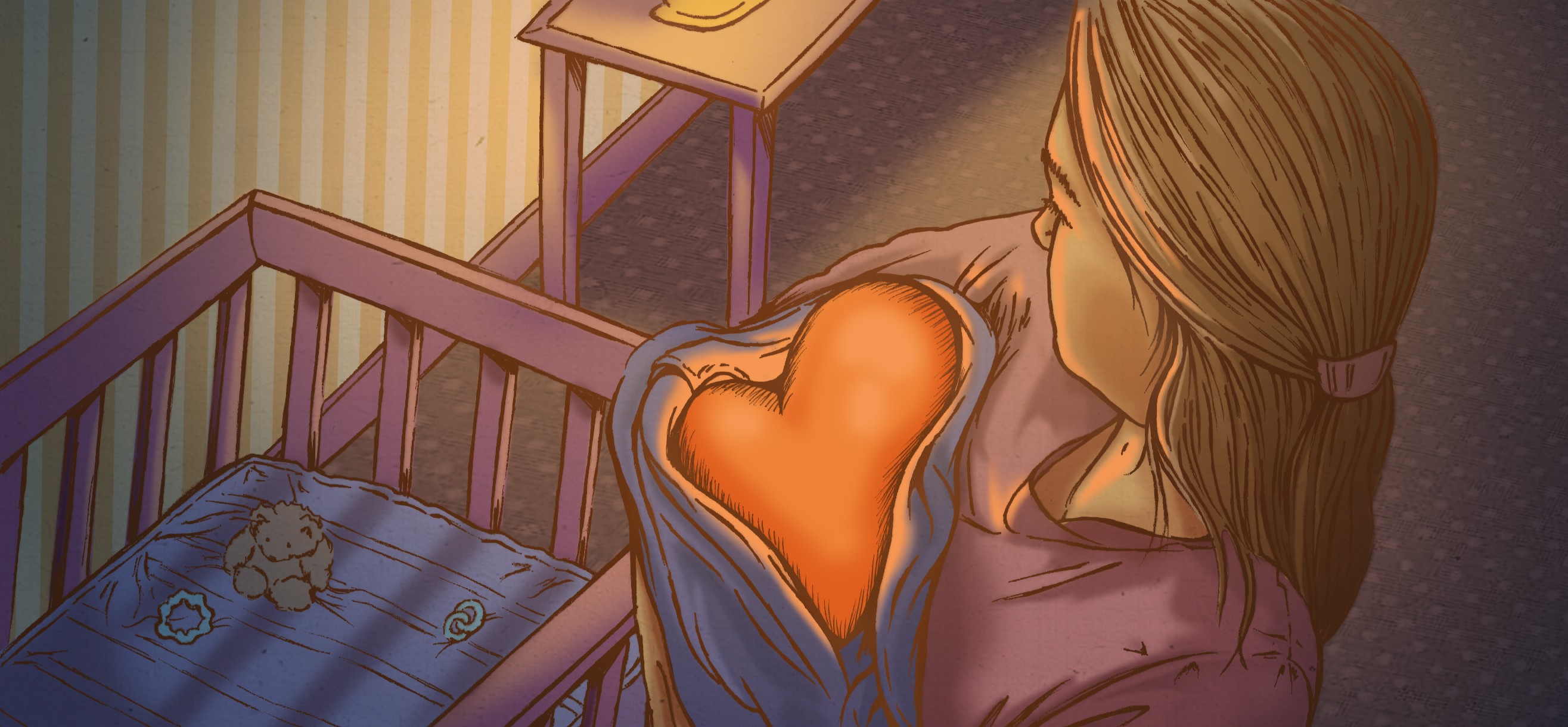

The morning after Lorenzo was born, I was lying in my hospital bed, cradling the baby in my arms and gazing at his sleeping face when he suddenly started to choke. On thin air. He hadn’t been nursing or anything, he just went from slumbering in that unreachable, newborn way to gagging.

I lay immobilized for a second or two and then I raced into the hospital hallway, holding Lorenzo and yelling: “Help me! Someone! My baby is choking!”

I was fully aware of how ridiculous this sounded and what a spectacle I was making but my panic overrode any sense of decorum. This was life and death.

A middle-aged nurse strode over. She was solid in her scrubs, and she walked like she meant business. Within a few seconds, she’d grabbed the baby out of my arms like a sack of beans and whacked him on the back, twice, with what seemed like excessive force. I winced as I imagined his spinal column shattering. But he remained in one piece, as erect as a newborn can be, and his gagging was replaced with bawling.

“That’s normal,” the nurse explained, handing the baby back to me and paying precious little attention, I noted, to supporting his head. “He’s just gagging on his amniotic fluid. They do that sometimes.”

She said it casually, like it was supposed to make me feel better. In fact, it had the opposite effect. I’d been prepared to protect my son from all sorts of choking hazards—loose change, hot dogs, paper clips—but later, in a few months, when I’d had a chance to hone my mothering skills. I’d never thought I‘d need to start now, right out of the gate, and that I’d have to also worry about him choking on stuff that was already inside of him. The very stuff that had shielded him from harm for the past nine months.

All of a sudden, the enormity of the enterprise before me slammed down on my shoulders. Holy Mother of God. There’d be things I would fail to protect him from. And not just the stuff I’d already, very diligently, worried about like clipping off his fingertips instead of his fingernails because I couldn’t see details that small. There was a whole world, a whole galaxy, of other stuff that I couldn’t protect him from, stuff that hadn’t even occurred to me, stuff I didn’t even know about. What the hell was I going to do now?

What I was going to do was hang my head and cry, the which I did right there in the hospital hallway, in my no-slip socks and pink polka-dot pajamas.

“You mean he’s going to do it again?” I sobbed, “and there’s nothing I can do to stop it?”

Without missing a beat, the nurse put her hand on my shoulder and ushered me back to my bed. She seemed so unfazed by my sudden crying fit, it gave me the strong suspicion that that hallway had seen far worse mental breakdowns. Working in maternity was probably pretty similar to working in the psych ward, except with bigger maxi pads.

“It’s going to be all right,” she promised, “A little gagging won’t hurt him.”

“But what if—” I sputtered. “What if he chokes so much he can’t breathe?”

“He won’t,” she replied. “I’ve never heard of that.”

That wasn’t sufficient reassurance for me. There was all sorts of shit you never heard about until it happened to you and then it was too late. I’d never heard about retinitis pigmentosa and yet, here I was, unable to see the tissue she was holding out to me until she finally shoved it right in my hand.

I blew my nose and took a deep breath. Too late to back out now.

“Tell me what to do, exactly, if it happens again,” I pleaded, “Step by step.”

“There’s only one step,” she replied, “Just give him a good old whack on his back.”

“But how will I know for sure that his airway is clear?” I pressed.

The nurse looked over in the direction of my roommate who was buzzing her call button insistently from behind the room’s dividing curtain. I’d been privy to my roommate’s every sound for the last twelve hours and despite the fact that I hadn’t caught a glimpse of her, I’d put together a pretty detailed profile: Polish, first baby, C-section, not much luck nursing, prone to sudden meltdowns herself. From the sound of the call button, there was another breakdown in the works, which meant mine had to be wrapped up.

“Look,” said the nurse, “if the baby’s crying, you know he’s not choking. So I guess if you really wanted to be sure his airway was clear, make him cry. Give his big toe a good squeeze—that’ll aggravate him.”

“OK,” I affirmed, “Got it.” If I have any suspicions that the baby is choking, any at all, I should make him cry.

Which is why I spent the first month of my infant’s life annoying him relentlessly.

I’d look over at the bouncy seat, where Lorenzo lay still, silent, and peaceful. Though this is most mothers’ dream, it was my call–to-arms. Why was the baby so preternaturally still? Clearly, he was not breathing. Likely, it was that damn amniotic fluid causing trouble again. Who knew how long he’d been like this? As I sat pondering, his brain might be losing oxygen! No time to undertake the subtle investigative measures I’d learned in infant CPR class like watching his chest rise and fall; I couldn’t trust myself to see the ever-so-slight movement of his chest anyway, my vision was so poor. No, no, this emergency called for the squeeze-the-toe test, approved by medical professionals as the quickest, most effective way to confirm baby’s respiratory health.

I’d squeeze the toe. He’d scrunch his placid face into a scowl and commence caterwauling. Mission accomplished. The baby was breathing. And, now royally pissed off.

Over and over again in the first weeks of my baby’s life, people were assuring me that if I trusted my mother’s instinct, I’d be fine and over and over again, I was finding that was a load of horse-crap. Maybe other mothers, ones with all their primary senses intact, had functional maternal instincts, but worry and a severe lack of confidence had caused mine to short-circuit. None of this mothering business was coming naturally. I needed a detailed instruction manual to do everything and sometimes, even that didn’t work. It was a classic case of the blind leading the blind.

From Now I See You by Nicole C. Kear. Copyright © 2014 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

Nicole C. Kear’s memoir, Now I See You (St. Martin’s Press): Order now the book and find more info at nicolekear.com.

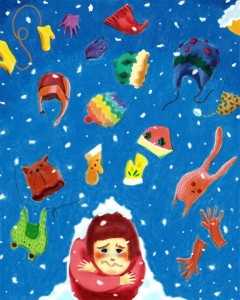

Like most two-year-olds, my daughter cannot abide winter gear. I can’t know for sure why hats and mittens are so anathema to her, though I can speculate. From her reaction’s epic proportions, I surmise the stakes are pretty high, so maybe it’s an object permanence issue and she believes that when she puts the mittens on, her hands cease to exist. Or it could be that the mittens prevent her from cramming Goldfish into her mouth like it’s closing time at the cheddar cracker bar. Whatever the reason, my daughter, affectionately known in these parts as Terza, will not keep hats and mittens on. Not if I sing like Elmo, not if I ply her with cookies. Not for any reason.

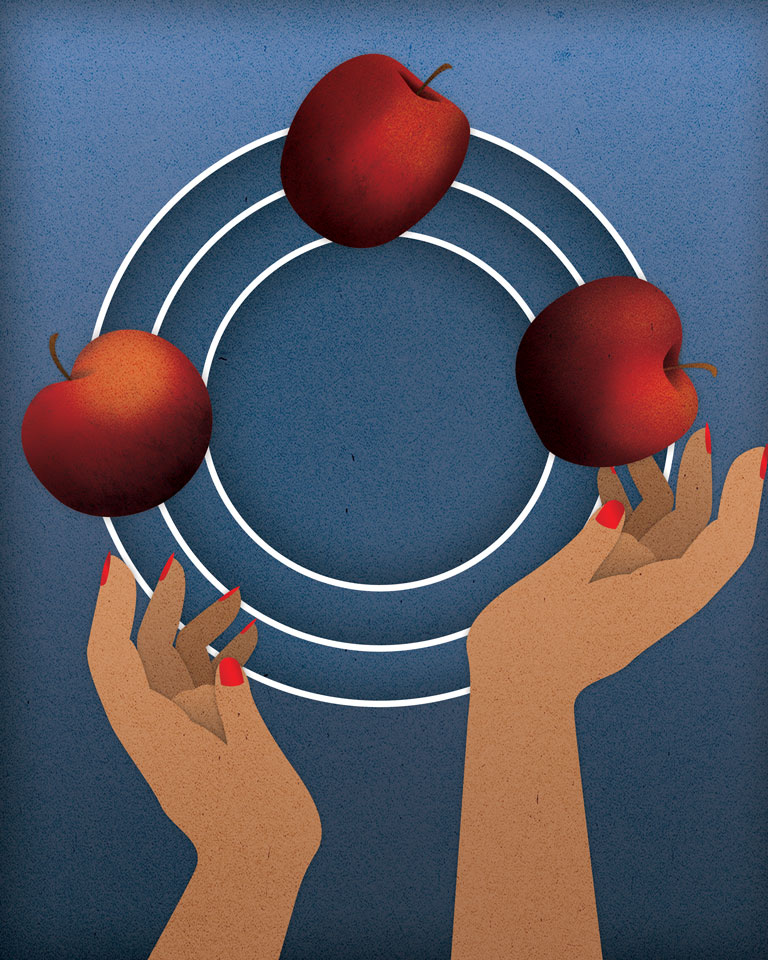

Like most two-year-olds, my daughter cannot abide winter gear. I can’t know for sure why hats and mittens are so anathema to her, though I can speculate. From her reaction’s epic proportions, I surmise the stakes are pretty high, so maybe it’s an object permanence issue and she believes that when she puts the mittens on, her hands cease to exist. Or it could be that the mittens prevent her from cramming Goldfish into her mouth like it’s closing time at the cheddar cracker bar. Whatever the reason, my daughter, affectionately known in these parts as Terza, will not keep hats and mittens on. Not if I sing like Elmo, not if I ply her with cookies. Not for any reason. Parenting in New York City is not for the faint of heart. Sure, there are conveniences that come with city parenting, and I ponder these frequently when I need a pick-me-up: Cheap takeout! Twenty-four-hour corner delis! Elevators in buildings! But the list of parenting tasks which are extra complicated or onerous or aggravating is long. Next year, for instance, I’ll have three kids in three different schools, making morning drop-off an epic expedition that would chill the blood of most suburbanites.

Parenting in New York City is not for the faint of heart. Sure, there are conveniences that come with city parenting, and I ponder these frequently when I need a pick-me-up: Cheap takeout! Twenty-four-hour corner delis! Elevators in buildings! But the list of parenting tasks which are extra complicated or onerous or aggravating is long. Next year, for instance, I’ll have three kids in three different schools, making morning drop-off an epic expedition that would chill the blood of most suburbanites. except from NOW I SEE YOU

except from NOW I SEE YOU I love the start of spring. Who doesn’t? Even the mildest winter brings its share of discomfort and inconvenience, but after a Polar Vortex Special like the one we’ve just had, after the months of suiting up like an Artic explorer, of traversing filthy mountains of sidewalk snow, of combatting epic, legendary cases of cabin fever, well, after all that, the first stirrings of spring are nothing less than magical.

I love the start of spring. Who doesn’t? Even the mildest winter brings its share of discomfort and inconvenience, but after a Polar Vortex Special like the one we’ve just had, after the months of suiting up like an Artic explorer, of traversing filthy mountains of sidewalk snow, of combatting epic, legendary cases of cabin fever, well, after all that, the first stirrings of spring are nothing less than magical. Young children are cute and lovable; they afford you a sense of purpose and meaning in addition to frequent bouts of heart-exploding joy. So I heartily recommend having one, or two, or hell, even three . . . but not if you want to avoid vomit and the runs and snot and fever and sores and other revolting things that I’m too demure to mention in print.

Young children are cute and lovable; they afford you a sense of purpose and meaning in addition to frequent bouts of heart-exploding joy. So I heartily recommend having one, or two, or hell, even three . . . but not if you want to avoid vomit and the runs and snot and fever and sores and other revolting things that I’m too demure to mention in print. Recently, I went swimming in sewage. Even for those who enjoy extreme sports, I don’t recommend it. Sewage stinks, in all senses of the word.

Recently, I went swimming in sewage. Even for those who enjoy extreme sports, I don’t recommend it. Sewage stinks, in all senses of the word. My kids put the “din” in dinner. I don’t mind the cacophony, most of the time. Being a city girl, I’ve always found the sound of silence deeply unsettling and if I had to choose, I’d opt for a vibrant racket over a tense, quiet meal any day. Of course, if there were a middle-of-the-road option, a little-light-conversation-peppered-with-soft-chuckling option, I’d go with that.

My kids put the “din” in dinner. I don’t mind the cacophony, most of the time. Being a city girl, I’ve always found the sound of silence deeply unsettling and if I had to choose, I’d opt for a vibrant racket over a tense, quiet meal any day. Of course, if there were a middle-of-the-road option, a little-light-conversation-peppered-with-soft-chuckling option, I’d go with that. Spring! The season of new life and rebirth! Unless, of course you’re a goldfish in our home, in which case spring is a time of death, plain and simple. Last spring, the death knell rang for the pet we’d come to know ironically as Survivor-Fish, as he joined his brethren on the other side. The good and bad news is that there were a lot of brethren to join—at least four fish from our house alone.

Spring! The season of new life and rebirth! Unless, of course you’re a goldfish in our home, in which case spring is a time of death, plain and simple. Last spring, the death knell rang for the pet we’d come to know ironically as Survivor-Fish, as he joined his brethren on the other side. The good and bad news is that there were a lot of brethren to join—at least four fish from our house alone. By the middle of January, I’ve packed up all the Christmas ornaments, wrestled the fake tree back into its box and tossed the leftover candy canes into the trash. Last to go are the holiday cards. As I archive our family’s card by sliding it into the file folder right in front of last year’s, I can’t help but remember the behind-the-scenes drama which went into the making of the card, a drama which is as much a tradition for our family by now as the card itself.

By the middle of January, I’ve packed up all the Christmas ornaments, wrestled the fake tree back into its box and tossed the leftover candy canes into the trash. Last to go are the holiday cards. As I archive our family’s card by sliding it into the file folder right in front of last year’s, I can’t help but remember the behind-the-scenes drama which went into the making of the card, a drama which is as much a tradition for our family by now as the card itself.