Reflecting on the FIFA World Cup 2014

The FIFA World Cup 2014 is currently taking place in Brazil for this summer month. It touches the emotions of the entire world. Where to watch it? The venues are endless in Park Slope. The place, however, doesn’t matter.

The FIFA World Cup 2014 is currently taking place in Brazil for this summer month. It touches the emotions of the entire world. Where to watch it? The venues are endless in Park Slope. The place, however, doesn’t matter.

Where to play it? It can very well be Prospect Park or Red Hook where Mexican street vendors offer us tacos and enchiladas… I remember growing up amid the Andean range in Cusco, Peru. No, we didn’t care if it was freezing cold or about the high altitude. We didn’t understand that concept. We were convinced that we had more red blood cells than other humans and were built physically to cope with those minor intangibles. We loved the game and were brought up understanding that it was the only game that really made mattered.

Recently I watched a movie titled The Cup. It was about two young Tibetan refugees arriving at a monastery, which was a kind of boarding school. The young monks were determined to watch the World Cup. After various comedic circumstances to achieve their goal, their leader, the Lama, is perplexed about the young monks seeming to move away from the teachings of Buddha.

Growing up around the Andean landscape, we did likewise. I remember the Spanish literature teacher doing her best to teach us Don Quixote. The knight-errant was, nonetheless, irrelevant for us. If Don Quixote was a dreamer inventing his own world, we were likewise, dreamers trying to escape the confines of the school and watch the games. Don Quixote? No. we didn’t care much about his own perceived foes. They weren’t ours. Furthermore, the poor fool was for us a perceived hero in his own mind, and the plot of the story was boring as well. No we weren’t ready yet to understand at that young age the existential and philosophical teachings of this knight-errant who rode an old horse called Rocinante. We were just ordinary children moving through the streets, creating mischief, and learning on the streets what was real and what was fantasy. We would, of course, find in the end a place to watch the World Cup. We were delighted and happy until someone would expel us from the place.

According to David Whelan from the Belfast Daily Telegraph “A street in west Belfast has caught the attention of passers-by after residents hung the flags of all thirty-two nations competing in Rio from their homes—even the St George’s Cross of old enemy England.” Likewise, most folks around the Andes will never root for Spain…it was an old colonizing enemy. We knew as children what they had done to us as colonizers—not only destroying the previous religious faith (sun worship), but using the existing temples to build their own churches.

Reality for the protesters against the World Cup in Brazil is also different. They do not see the World Cup benefiting the folks living in the “favelas,” where living conditions counter the happiness surrounding the World Cup. The real world that surrounds us remains uneven, not flat (full of Starbucks) as a book has suggested.

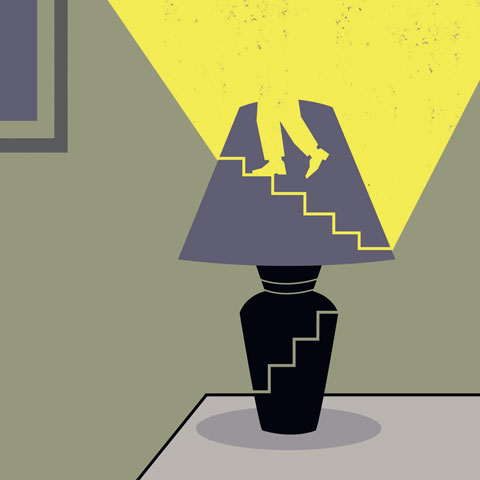

The World Cup in Brazil does not cure the wounds of the past and those of the present as Franklyn Foer explains in his book How Soccer Explains the World. It has indeed become a religion for many around the world. Thus, the World Cup 2014 unites us briefly, and in a tribal way we carry our national jerseys. But, is it all real or a distraction for a world being constantly engineered and controlled? The tribes of the world, in that context, are allowed this moment to unite for a month and around their flags and national anthems. Is it all an illusion that we have created? Like that of Don Quixote?

The movie The Cup makes me also wonder about the team the two monks where rooting for. Was it Brazil? Do Tibetan children have a team to root for? Like those two young monks, we children in the Andes cheered for Brazil. I am sure about it. We wanted them to win it…but why? It was because Brazil was a tribe closer to our own and their game wasn’t mechanical. It was more Pina Bausch dancers than that of Twyla Tharp. It was Sergio Mendes’ “Mas Que Nada”, not Wagner’s “Valkyries.” The Brazilian game had more heart than brain in its movement. We children understood that. It was knowledge by observing. We related to that kind of game.

So now, many years later I understand the young teacher’s agony (Teresa was her name) in wanting us to understand the meaning of illusions and dreams through the life of a knight-errant and his tag-along Sancho. A knight-errant determined to fight his own dreams. I understand the teacher’s agony, but ours was to escape the confines of the school and live another dream…the dream was the World Cup. It was the only game that made sense in our young lives.

The account of the Storyteller of Shimokitazawa continues in Park Slope, Brooklyn: The Sock Man

The account of the Storyteller of Shimokitazawa continues in Park Slope, Brooklyn: The Sock Man It is located in the Roppongi section of Tokyo, known for its night club scene. On the second floor of an old building is Geronimo, a bar that has not much to offer except for few wooden communal tables for expats who mingle in the bar.

It is located in the Roppongi section of Tokyo, known for its night club scene. On the second floor of an old building is Geronimo, a bar that has not much to offer except for few wooden communal tables for expats who mingle in the bar. This bar is in Park Slope, Brooklyn and it is called The Black Horse Pub. I went there to watch a soccer game which is a qualifier for the World Cup to take place in Brazil in 2014. Everyone in the world is playing soccer in order to be one of the thirty-two qualifiers. It is a big thing.

This bar is in Park Slope, Brooklyn and it is called The Black Horse Pub. I went there to watch a soccer game which is a qualifier for the World Cup to take place in Brazil in 2014. Everyone in the world is playing soccer in order to be one of the thirty-two qualifiers. It is a big thing.