And Learning from the Experience

I made a tough call. I had no idea what I was doing. How could I? It was 2001. I was 26 years old. I had recently graduated with my law and social work degrees, and I was working as an attorney for children. I mostly represented children in custody and visitation cases in Manhattan Family Court. At one of their parent’s insistence, my teenage child client told me their other parent threw a shoe at them, and showed me a mark on their leg.I wasn’t worried for the child’s safety. I consulted with my supervisor, and made a report to the child protective services (CPS) hotline because I thought I was required to. I didn’t know better. Now, I do.

F

or almost 60 years, professionals, like me, throughout New York City, New York State and the United States, have been making reports to CPS like our livelihoods depended on it. Over 4 million reports were made in the US last year, with 51,000 of those reports right here in New York City. Few of these reports relate to families in Park Slope, but not because Park Slope parents are perfect. We’re far from perfect, but very much protected by privilege.

Most reports come from professionals who are trained to believe that if they don’t make these reports they will lose their license, get sued, and go to jail (which hardly ever happens). What I didn’t realize when I made that tough call in 2001, is that these reports are more likely to cause harm than good to the families and communities professionals think they’re protecting.

The policy of mandated reporting was adopted across the country in the 1960s. The original policy was championed by pediatricians who sought the opportunity to identify child physical abuse and urge responsive government response that would protect children from further harm. The expectation in those days was that parents would get a talking to; they would learn the error of their ways; kids would be safer. If the parents didn’t “get it”, children would be removed from their care until they “got it”. In 1965 there were about 250,000 children in “foster care”. Then, things got out of control.

In the early 1970s, against the advice of lawyers, social workers, judges and other experts, the United States Congress passed into law the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (“CAPTA”) with problematic language. CAPTA required as a condition of federal funding that states adopt laws that required a multitude of professionals, not just

doctors, to report a whole litany of concerns to child protective services, not just physical abuse. Most notably, CAPTA includes a requirement that mandated reporting laws include the reporting of “neglect”. The definition of neglect is closely associated with the conditions of living in poverty. Within 5 years of passing CAPTA, and requiring reports of neglect, there were over 500,000 children in foster care.

Many saw this rise in children in foster care as a success; more children would seem to be getting protection. But, the families impacted from these policies knew better, as did the professionals working in these systems. The most esteemed of these professionals called for the exclusion of neglect cases from the mandate to report. They explained: “[a]s a result of the often vague definitions of neglect and the consequent discretion granted reporters, it is probable that cultural, racial and economic distinctions between the reporter and the reported will influence and unfairly bias the reporting of certain groups of children” (Sussman, & Cohen, 1974). These experts explained that most professional reporters are white and middle/upper class; most families reported are poor and from cultural and racial minority groups. These experts argued that a law that required professionals to report neglect would hurt poor families, especially of families of color. They were right. Recent research finds that more than half of all Black families in America will be investigated by CPS before their children reach adulthood; only ⅓ of White families will have the same experience. Research suggests implicit and explicit racial bias factor into this disproportionality, as does the confluence of neglect and poverty.

Shortly after adding neglect to the mandate, reports of neglect made up the vast majority of reports to child protective services hotlines. Even today, neglect reports make up 60-70% of cases investigated by New York City’s Administration of Children’s Services (“ACS”). People without direct experience don’t realize that neglect is what CPS is most likely responding to, because the media focuses on high profile cases of extreme physical and sexual abuse, which happen to be really rare.

Substantiation rates of all reports are abysmal. Nationally, only about 1 in 5, or 20% of all reports are substantiated after investigation. In NYC, that rate in 2023 was 29%. The substantiation rates of neglect are even lower. Mandated reporting policies have been creating problems for a long time.

In 2004, I co-chaired a committee on mandated reporting sponsored by Fordham University. This group met monthly to discuss policy and training initiatives that would improve the practice of mandated reporting, so that the associated harms to low-income families and families of color could be minimized. We talked about statistics and training protocols; we analyzed statutory and regulatory language; we debated the best courses of action towards change. The dominant voices in the room were that of attorneys; the social workers were more reserved; the systems-impacted parent members of this committee were generally the least engaged, except for one particular voice. This voice made waves.

As a co-chair of this committee, I had an agenda to follow. I had tasks that needed to be addressed during and between meetings. I used my facilitation skills to get consensus, so we could make decisions and move on. The voice that made waves had other goals, namely to not sit idly by while the “experts” made recommendations that would impact others, not themselves.

This voice was of a system-impacted parent. They had been reported to ACS by their child’s schools multiple times. Most reports against them were unfounded. The allegations were never of physical or sexual abuse. The school officials were frustrated that the parent insisted they knew better than school personnel about the needs and ability of their own child. The school personnel wanted this parent to simply do whatever they asked of them, but that was clearly not the parent’s style (as I could attest from their participation in our meetings).

No matter what our committee was discussing, this parent would insist that we were missing the point. They insisted that mandated reporting couldn’t be made “better”, but that we needed to eliminate it. We ignored them, but they were not dissuaded. They would tell us that low income families of color, like their own, didn’t trust mandated reporters to help because reports brought pain, not assistance. They reminded us over and over and over again that the vast majority of reports by mandated reporters were actually unsubstantiated after investigation; every report brought trauma and stress to a family, likely already experiencing stress and trauma. Reports didn’t bring help; they brought hurt. As anyone with significant experience in task oriented meetings can explain, when there is someone in that meeting who doesn’t share the same goal of getting the “task” done, the rest of the group will evidence their disdain. In our group, whenever we would get close to a decision point and received most members’ assent, we would collectively hold our breath, turn to this parent, and collectively roll our eyes when they opened their mouth to remind us we were completely off our rockers. These meetings were exhausting for me, and then I started to listen.

I started to listen to this parent, and then to more system-impacted parents, like Joyce McMillan, of JMAC for Families, a family advocacy organization. The more I listen, the more I learn; the more I learn the more I share the concerns of those impacted. Without listening, I’d never really know. How would I? I am a White, upper-middle class, woman who was never subjected to government investigation of my parenting skills. The professionals I interact with do whatever they can to help me and my family members; they don’t question my judgment, or assume I’m not prioritizing my child.

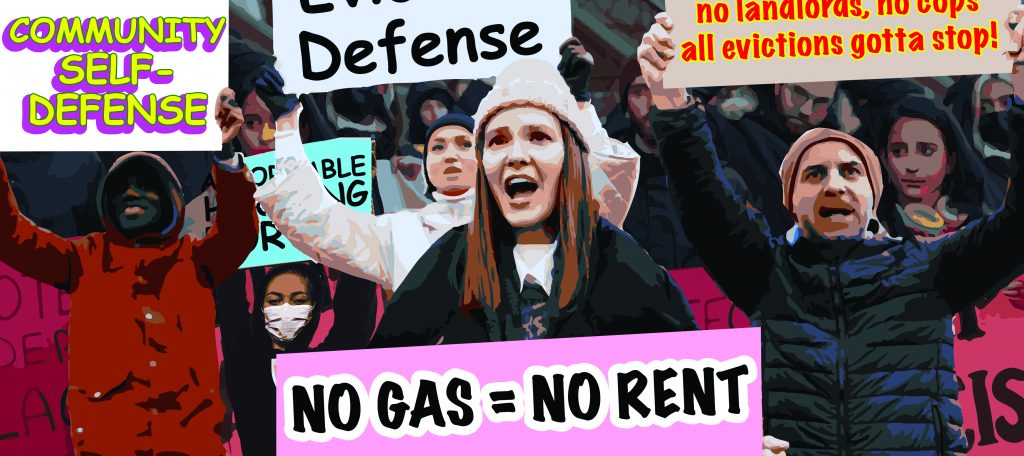

After a lot of listening and two decades of conducting related research and training, I no longer think mandated reporting can be fixed. I think mandated reporting is a system broken beyond repair. Now, I use my voice and skills to support Joyce’s call for replacing mandated reporting with “Mandated Supporting”. Under “Mandated Supporting”, professionals would be required to offer services and assistance when they are concerned about a child or a family; norequirement to call CPS, but a report to CPS is available if other help won’t address the need. No tough call here.

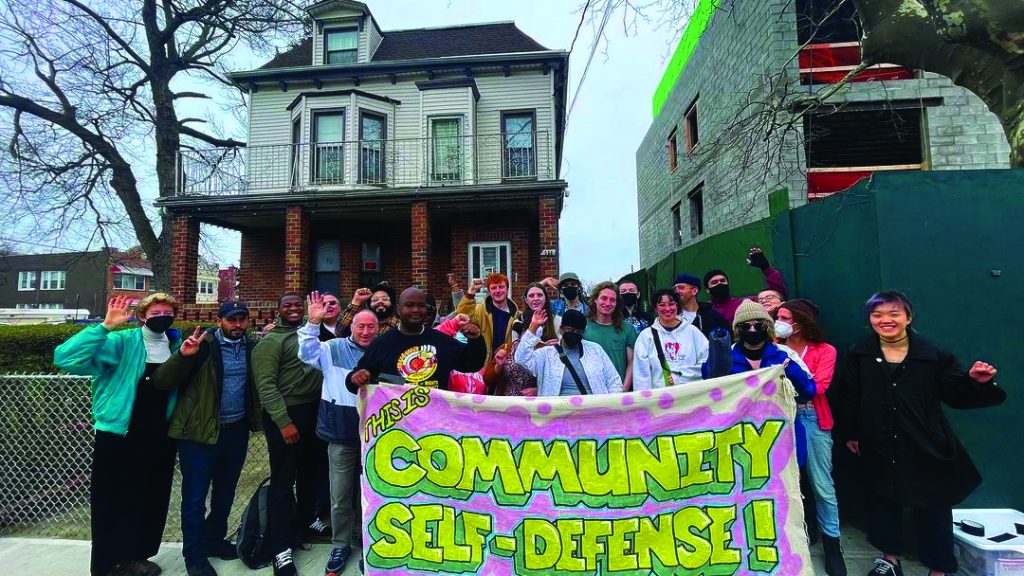

Moving towards ”Mandated Supporting” is exactly what we’re working towards in a new organization I’m a co-facilitator of: the New York Mandated Reporting Working Group (NYMRWG). We are a group of professionals, practitioners and people who have been directly impacted by CPS. The goal of the NYMRWG is to raise public awareness about the realities of mandated reporting and develop solutions to narrow reporting laws and the invasive investigations they trigger, while refocusing on community-based support services, separate from government intrusion into families.

The NYMRWG wants to protect children from harm, just like the pediatricians of the 1960s who created the original mandated reporting policies. However, we believe that centering this goal on services provided by a government institution with a history of racial and social injustice has been a disaster, and only makes family and community conditions worse.

Twenty-four years ago, I made a mistake. I called the CPS hotline because I thought I had to; because I thought it would help. I didn’t have to, and it didn’t help. I made a tough call, and it was the wrong one. I’m hoping if more people learn about the problems with the current system, and demand responsive changes, there won’t be any tough calls to make, just support to provide.

Reference material available upon request: kathryn@kraseconsulting.com