Fields, courts, and stadiums swell with emotions from high-intensity moments, and athletes often crack under the pressure. What if we set our fear aside and embraced inevitable failures on our paths to success? We may be surprised by the opportunities that appear by removing perfection from the playbook of life.

As I write this, it is playoff time for many sports at professional, collegiate, high school and recreational levels across the country. The New York Knicks recently lost to the Indiana Pacers in Game 7 of the NBA Eastern Conference Finals. The New York Rangers are playing in the NHL Eastern Conference Finals Series against the Florida Panthers. Park Slope’s own public high school sports team, the John Jay Jaguars, are representing in the Public School Athletic League (PSAL) playoff tournaments, as well. The Jaguars Girls fencing team took 1st place citywide in Fencing-Foil; Boys volleyball is in the semifinals; baseball and softball are starting their playoff bids. It is exciting to watch playoff games and hope your team succeeds. But so much of the energy around these contests seems to be defined by mistakes, both as they happen and then for stretches of time after.

There is a lot of pressure on athletes, and the officials that judge them, to be perfect, but perfect is not possible. Any successful, or simply satisfied, sport-involved person understands that mistakes have to happen. Heck. Any successful, or simply satisfied, human being understands that mistakes have to happen. Albert Einstein said: “[a]nyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” Making mistakes is such an important part of the road to success that Billie Jean King told us: “[c]hampions keep playing until they get it right. Then they play more.” Mistakes are inevitable. So, if mistakes are clearly a matter of life, why do so many people act like mistakes are horrible? Maybe it’s because mistakes can be so devastatingly memorable.

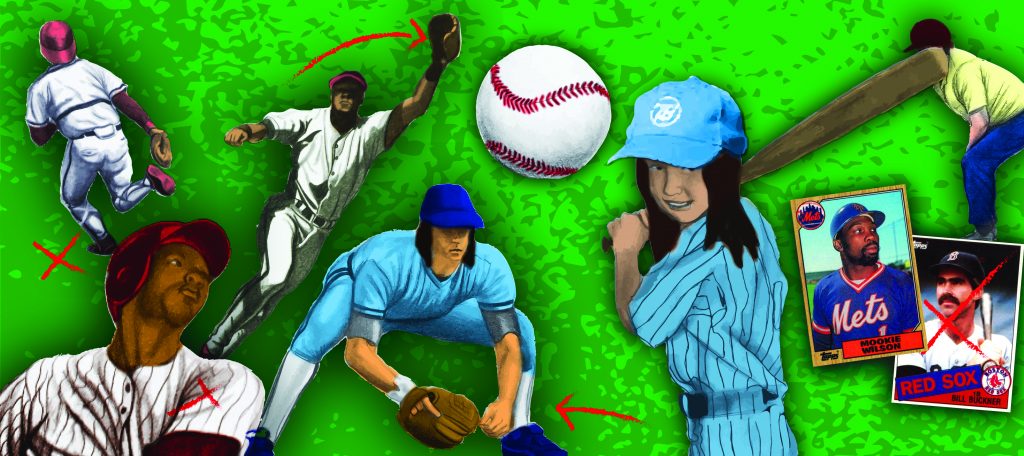

I was only 11 years old on a fateful Saturday night for New York Mets fans in October 1986. I was awake, though bleary-eyed, watching the 10th inning action of Game 6 of the World Series between the Mets and Boston Red Sox. With two outs, the Mets battled back from a 3-5 deficit thanks to singles from Gary Carter, Kevin Mitchell and then Ray Knight. But it was the ball hit by Mookie Wilson that rolled right through Bill Buckner’s legs that is still talked about, and even academically studied, almost FORTY YEARS later. Buckner’s error allowed Ray Knight to score the Mets’s winning run.

The lore is that the Mets won the World Series because of that error. But, that’s not even close to reality. There was still another game to play before the Mets would take the World Series in Boston. The Mets won the World Series because of a combination of successes and errors. Buckner’s error actually only determined that one play. If he hadn’t made the error, and instead got Mookie out at first, the game would still have been tied at the end of the 10th. Ultimately, it would have been someone else’s fault when the Mets won.

We are so hard on each other and ourselves when we make mistakes. Boston fans relegated Buckner to pariah status, and he never recovered professionally. In his death, his numerous obituaries highlighted this error over his many successes and achievements. It often seems like people enjoy hating others for their mistakes. All that negative energy is destructive internally, and externally. Over my many years in sport as a player, coach and sports official, I have seen plenty of coaches, players and spectators yell at players and officials of all ages after a mistake, saying things like: “what’s wrong with you?” or “why did you do that?” or “what were you thinking?” and “are you stupid?” I’m never quite sure why these words are spoken aloud. I don’t see any way that these comments could help anyone process a mistake they just made.

Others take the opportunity to make light of mistakes, by laughing or imitating. These attempts are often intended, or received, as belittling to the one whose error is being highlighted. The one who made the mistake will often be the first to make fun of the error. My son often makes such humorous efforts on the volleyball court. If he misses a clear opportunity, he will roll on the floor unnecessarily and shake his head as if he doesn’t know what went wrong… then smile and laugh. I usually see these responses in my son and others as a coping mechanism, to shield themselves from the potential humiliation offered by others that often comes after their mistakes. These self-deprecating expressions are also easiest to offer when the stakes are low.

I can almost understand needing to groan and moan, or even laugh, when professionals in an athletic environment disappoint you by not being perfect. However, when you think it’s appropriate to similarly protest a kid who isn’t living up to your expectations, it’s time to reevaluate your expectations, and truly accept the reality of mistakes.

There are significant consequences when we make a big deal out of mistakes. One of the main reasons kids leave sports is because of how grown ups (and their friends) react to their mistakes, even at a young age. All the research tells us that children develop best in environments where they are not afraid to make mistakes. When kids are encouraged to try, and supported when they fail, they learn that mistakes are necessary for growth. The cool thing is, once a child gets the kind of support that acknowledges mistakes as part of the process, they actually make FEWER mistakes in the future because they don’t have the added stress on them to perform; they just do it.

Now, I’m not saying that it’s best to ignore mistakes. I think mistakes should be identified, acknowledged, and processed. If the goal of this interaction is to get correction in the future, I would recommend this process be done with kindness and grace.

As I started my role as a baseball/softball umpire and volleyball referee, I was worried about making a mistake. I knew mistakes would come; I’ve seen enough sports officials make errors, and had no expectation that I would break the mold and be perfect. My fear about mistakes had to do with how others would respond to them. Would people still respect me? Would they argue with me? Would they consider hurting me? I processed these concerns with anyone who wanted to hear me. It was during one of these exchanges that someone told me of the experience of a professional sports official they knew. Early in this official’s professional career they acknowledged a mistake they made and had an eye opening interaction with the impacted professional athlete. As they told me this story, I expected the story-telling was designed to make me feel more confident. However, that was not at all the point. It was a warning.

When the professional sports official in question was new to their craft, a very famous player in their sport got upset at the new official for “missing a call”. The new official took this player’s comments to heart and reviewed the recording of that play numerous times over the next few days. The official determined the player was right; the new official HAD missed the call. The next time the official was set to work a game for that player, the official approached the player to make a mea culpa. The official expected the player to thank them for their thoughtfulness and appreciate their retrospection. Instead, the player simply said something to the effect of: “Don’t do it again.” Ouch.

That professional athlete was being unreasonable. That official has and will continue to make mistakes. Now, those mistakes are more likely to be reviewed and overturned through replay/challenge structures that are more prominent than ever. But, no matter how many times an official’s call is overturned, they will still make mistakes, because mistakes are inevitable. (Within the decade much of the ado related to the mistakes of sport officials will likely be moot as technology develops to provide ways to make these calls with scientific accuracy.)

Some players play it safe so that they don’t make mistakes, but they still suffer the wrath of others. Think about a baserunner ignoring the coach’s steal sign, a center driving with the ball down the lane passing the basketball back to the perimeter, or an outside hitter tipping a tightly set volleyball, to name a few. Some coaches challenge these players for not “playing it hard” on every play. In these moments, these players will tell you that they have made a calculated decision to not go hard because they believe going hard would lead to an error. They also believe that if they go hard and make that error, they will be further penalized by the coach, and/or the crowd. So, they make a calculated decision to avoid the error, but also potentially miss an opportunity. Having watched, and made, these kinds of decisions in real-time, these players are usually making the best decision they can. Coaches, fellow players and spectators should support players to make the decisions they are most comfortable with.

Other athletes seem to give it their all on every play, even when the chance of success from their effort is slim. In these moments, it looks like the player just wants to get the mistake out of the way. I see these kinds of kids all the time in baseball and softball games with the under 12 year olds in Prospect Park. These players get to the plate, settle in quickly, and then swing at the first 3 pitches they see. I observed one such player this past weekend. Before each pitch was thrown, the player uttered loud enough for me and the catcher to hear: “Hit me. Come on. Hit me.” When I first heard it, I wondered what the kid was thinking. But I quickly realized that as the player swung at each incoming pitch no matter where it was, the player wanted out of that pressure filled role as soon as possible. They welcomed a potentially painful hit-by-pitch to avoid the stress of the inevitable personal mistake.

If you’re like me, you are likely to watch a few hundred mistakes happen in real time in athletic contests in the next few days, weeks or months. Do everyone a favor: emotionally prepare for these mistakes and then accept their eventuality. Some mistakes will benefit the team you’re rooting for, others will sting as they relegate your team to the status of “loser.” Instead of focusing on the mistakes, save your energy to celebrate a success, however broadly you need to define it.