In case you’re wondering what a “NIMBY” is: “NIMBY” stands for “Not In My Back Yard”. The characterization of a NIMBY is someone who opposes a proposed development in their local area, that they would likely support if built somewhere else. Calling someone a NIMBY is usually intended to be an insult; calling someone on their hypocrisy. That’s definitely how it’s been used against me on Twitter. You see, I was recently an active and vocal opponent of a rezoning application that, literally, impacted my own backyard. However, there is a lot more to NIMBYism than internet trolls have time or context to appreciate. It’s actually a long story, so this is the first of two parts. The second part will be in the next installment of Park Slope Reader in Spring 2023.

I’m a lifelong Brooklynite. I’ve been a homeowner in Gowanus since before it was trendy. The area has changed a lot in my lifetime. Change is inevitable, and often beneficial. But not all change is good. And, therefore, concern for change can be reasonable, even if characterized as NIMBYism.

When my Brooklyn-born/bred husband and I purchased our small Gowanus home in 2003, our Brooklyn-born/bred real estate attorney made sure we knew that a 11215 zip code on 8th Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenues was NOT Park Slope. We knew it wasn’t Park Slope; we couldn’t afford Park Slope.

Many Brooklyn born/bred family members doubted our decision to buy in Gowanus, and for good reason. Gowanus was best known for its contaminated waterway, as well as rats, drugs and sex workers. Gowanus was not known for its quality housing. Gowanus is not flush with gorgeous Brownstones, coffee shops, or real estate offices. Our particular block in Gowanus has 12 understated houses, along with 50 lots involving significant manufacturing and business activity. Industry on our block includes a commercial carting company that does NOT smell good in the summer, a woodworking shop that is very noisy, and lots of truck traffic.

Our block, and much of Gowanus, has been zoned for manufacturing purposes since the early 20th century. Our own house, built shortly after the Civil War, is the oldest structure on the block. Since our house was built before zoning rules even existed in NYC, it is considered “grandfathered” for “non-conforming use” as a residential property; the other 11 houses on the block are similarly characterized. While we are allowed to live in these existing structures as homes, we cannot add residential square footage on our properties. Living in houses built a long time ago, to meet different needs, can be difficult. As a result, many of us have considered building small extensions, or even taking down the structure that exists, and rebuilding a better home. We’re not allowed to do either. We are only allowed to expand, or rebuild, for manufacturing, or related non-residential, uses.

Our brick house was originally built 17 feet wide, 25 feet deep and 3 stories tall around 1866 without plumbing or electricity. When the local municipality built the first brick sewer in the middle of the street (still in use today), they couldn’t place the sewer underground, because Gowanus is topographically a swamp. So, in around 1880, the City built the sewer on top of the existing ground, and built the street on top of the sewer. As a result, the 3 story existing structure became a 2 story structure, with a full “English basement”. Around 1910, the owner built a wood-frame extension on the side of the house, literally leaning it on the wood-frame house recently built next door. The street-facing brick facade of the extension on our house makes it look like one contiguous, brick home, 25 feet wide; it is not. Three (3) of the homes on our block are built out of brick. The other 8 are wooden frame structures, some with a first floor framed in brick. Most, like ours, have old stone foundations.

Much of the rest of our block is made up of 1-4 story brick factory-type buildings. In 2003, the largest factory buildings on our block were operating, sometimes 7 days a week, making sweaters. Around 2005, a line of tractor trailers and large cranes brought enormous machines, some 30 feet long, out through deconstructed windows onto flatbed trucks. The machines were destined to continue their useful lifespan in Mexico. The machines and factory workers were largely replaced by artist studios and small businesses. In 2008, The Bell House bar and performance space opened up around the corner. Things were changing in Gowanus.

By 2010, nobody was doubting our real estate choices. Growth in local feral cat colonies largely diminished the localized rat population. More active streets at night pushed out the sex workers. Drugs remain a perennial issue, but not significantly impacting the local quality of life. And, after centuries of problematic industrial use, the Gowanus Canal is being “cleaned” up. Change can be great.

Smack dab in the middle of some of the most expensive residential neighborhoods in the country EVERYONE wished they could own a piece of Gowanus. Running out of space to build in Downtown Brooklyn, and limited by the landmarking restrictions of Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens and Park Slope, real estate developers drooled at the opportunity to buy and build along the banks of an EPA defined “Super Fund Site”. Add to the pressures NYC’s housing affordability crisis, and residential development in Gowanus seems like a win-win situation. But, there are many potential losers, including some outside of our control, like topography and the environment.

There is a VERY GOOD reason why Gowanus was never a residential stronghold: Gowanus, ecologically speaking, is not a good place for housing. It’s better suited for other uses.

The area was ideal for use by the early manufacturing industry since the Gowanus canal provides an easy route to move supplies and products to and from New York Harbor. The canal also provided the early manufacturing industry access to the water they needed to clean and cool their equipment. The canal and the area surrounding it were also deemed great places to dump dangerous industrial byproducts. After 150 years of industry in Gowanus, there is a lot of contaminated water and land.

For the manufacturing industry, Gowanus was ideal. For housing, not so much. Gowanus is located at the bottom of two hills, only about 10 feet above sea level. Urban planners have long avoided locating housing in low-lying areas close to water. As NYC developed, the most valuable residential properties in Brooklyn, like those in Park Slope, Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, and Brooklyn Heights were high above the water; the names of these neighborhoods actually reflect their altitude.

When the government finally chose to invest in affordable housing development, they found the cheapest land with the lowest demand, in Red Hook, Gowanus, the Lower East Side, and South Bronx. These areas are all close to the shore line, and prone to flooding like the devastation suffered 10 years ago in the aftermath of Super Storm Sandy. These areas are not just vulnerable to storm surge from the shoreline, but endangered by the rising water table, as well.

The old Gowanus swamp exists as the current water table, fewer than 10 feet under the foundation of our 8th Street home. In the summer, when the water table is highest, some of our neighbors have water coming up through cracks in their basement floors. As the water table is expected to rise with continued impacts of climate change, there is little to be done to protect our properties from this threat. The old stone foundation of our own home is endangered from below. Storm surge and water tables aren’t our only issues, though; we also have to tackle sewer backflow and overflow.

Soon after we purchased our home in 2003, we learned from a NYC Department of Environmental Preservation (DEP) official that the brick sewer on our block was “really old”, and insufficient. Gowanus residents and businesses have long known these inadequacies. We have “check valves” on our sewer lines so that sewage doesn’t invade our basements when rain overwhelms our sewer system that combines household waste with stormwater. We also have submersible (aka sump) pumps that push out waste water when it penetrates our property even with our best efforts against it. We lend each other wet/dry vacuums as needed. The DEP official, way back when, told us we needed a new sewer… It’s been almost 20 years since that DEP visit, and still no new sewer.

Every year, at least one neighbor suffers catastrophic property loss due to sewer backflow after a storm. Last year, a new non-residential neighbor just completed renovation of a beautiful performance rehearsal space when the sewer overflow from Tropical Storm Ida ruined their efforts, and set them back months on their project. In big storms, like Sandy and Ida, sewer and utility manhole covers are known to fly up 20 feet in the air under pressure, as geysers of stormwater mixed with sewage flood the streets and sidewalks of Gowanus. For these reasons, many in the area know to avoid 9th Street and 2nd Avenue after storms. It can take hours before the street is passable to foot and car traffic.

Even with these concerns, I understand the need for change, and know Gowanus presents an opportunity. In 2013, I participated in a series of community forums called “Bridging Gowanus”. Through this Pratt Institute moderated initiative, residents and businesses came together with our elected officials, and envisioned a better Gowanus. We aimed for moderate residential development with a focus on affordable and accessible housing, thriving business and creative communities, and increased green space and playscapes. Most importantly, we held high hopes for long-overdue significant investment in infrastructure. We got very little of what we worked hard to envision.

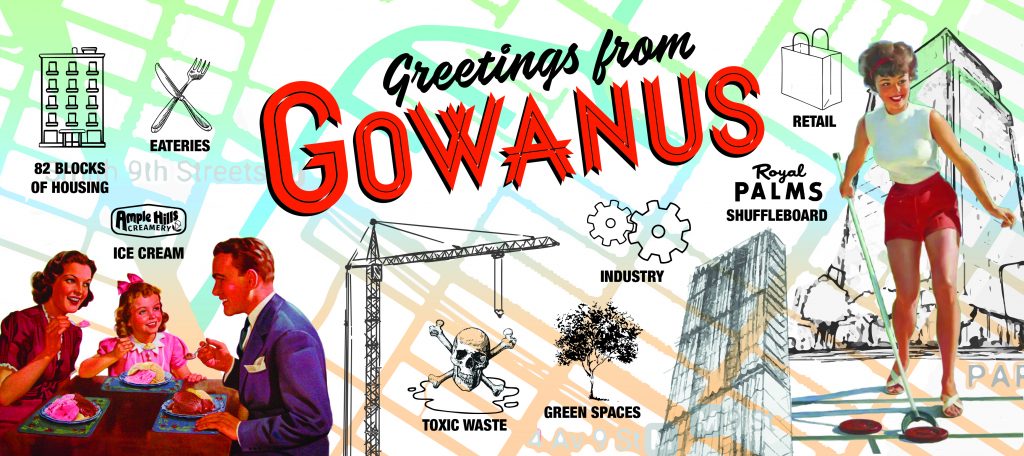

What we got was the “Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning Plan”, passed by the New York City Council in 2021. This plan will bring 8200 new residential units to an 82 block stretch of the area. More than 5000 of these units will be luxury rentals and condos; not at all what the Bridging Gowanus initiative envisioned. About 3000 units will be “affordable”. Around 2000 of the “affordable” units will have rents ranging from $2000-4000 per month, for households making between $70,000-200,000 per year. Fewer than 1000 of the affordable units will be accessible to low-income families. The influx of luxury units will threaten existing affordable units in and around Gowanus, especially those in nearby rent stabilized buildings. As has happened in other areas of the City, private landlords often push out tenants paying below-market rent when the local average rents substantially increase.

NYC needs to meet the demands of our growing population by building more housing. We also need MORE than housing. The Gowanus rezoning plan lacks adequate investment in schools, green spaces, transportation, and other community services. Additionally, the plan completely ignores the fact that almost all of the 8200 housing units being added to Gowanus are being built in a floodplain, with a grim climate outlook, next to a toxic Superfund site.

I actively challenged the Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning Plan. I worked with, and supported, community groups that yearned for the rezoning process to heed their concerns. We were all called NIMBY’s. We were called the “greatest threat” to the project. But the negative media coverage we received rarely acknowledged our real concerns. We weren’t saying no to any and all development; we weren’t saying no to new housing; and we DEFINITELY weren’t saying no to affordable housing. We were saying “hold up”. We were saying “there are better options than what you’re proposing”. We were saying “there are people living and working here with little power, who are going to be impacted in really bad ways”. But, we were largely ignored, and the plan was passed.

In May 2022, Gowanus community members raised concerns about the impact of pile driving at some local construction sites, as developers raced to start construction to take advantage of a sunsetting real estate tax abatement program. Neighbors brought attention to how the pile driving wasn’t just continuously loud throughout the day, but it was also shaking the ground for blocks. Even more concerning, the work was causing strange odors in the area. You see, the site once held a natural gas plant, and the land was known to be contaminated with coal tar, a carcinogenic, industrial waste. Even though many elected officials insisted on quick action to respond to community concerns, there was no assurance that the construction was adequately protecting the site, or the community, from dangerous contamination of toxic vapors.

Two months later, kids playing in a nearby playground, again, complained about a disgusting smell. At this point, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation confirmed that instrument readings at a particular site found volatile organic compounds exceeding acceptable levels. The work was temporarily halted, but later restarted. If it wasn’t for the complaints, would the community even know there was a problem?

Sometimes NIMBY’s are privileged people who don’t want change. But, I bet more times than not, NIMBY’s are people with important experience whose concerns should be heeded. In part 2 of this piece, available in the next edition of the Park Slope reader, I explore a more recent, and more personal, experience where my own NIMBYism was really brought to the surface.