When my son was in second grade, his teacher told him about Poem in Your Pocket day.

“Everyone brings a poem in their pocket,” he explained to me later. “And then we read them to the class.”

I loved this. It was very nearly the greatest thing ever. But if there’s one thing better than having a poem in your pocket, it’s having a poem in your brain — a poem learned by heart.

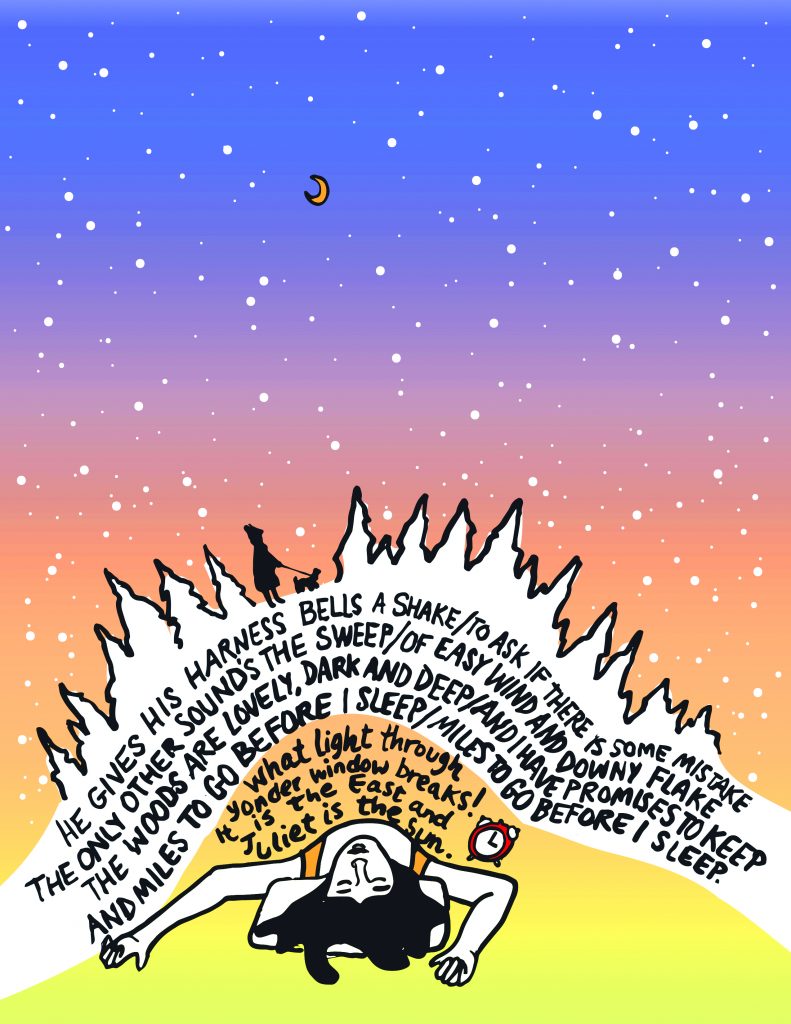

Recently, I woke in the middle of the night and discovered that I could recite Romeo’s balcony scene soliliquy in its entirety. You know the one.

“But soft!” it begins, “What light through yonder window breaks! It is the East and Juliet is the sun.”

I’m not sure what caused me to think of this line around 3am on a Wednesday, except that I think of many things at 3am on Wednesdays. Sometimes it feels like I do as much thinking in the middle of the night as I do in the middle of the day. I definitely do the lion’s share of my worrying in the wee hours. But on this occasion, instead of my mind conjuring an apocalyptic scenario, it made a lovely line of Shakespeare materialize. What shocked me wasn’t that some trigger had knocked loose a long-forgotten line of poetry, but that that it had knocked loose the whole speech, which played out, each word following the next fluidly, as if I’d only committed it to memory that morning, as opposed to twenty years before.

It was a wondrous, triumphant feeling to discover the jewels of poetry still there inside my brain. It was like uncovering a secret room full of treasure, whose door had been soldered shut. I witness this feeling every time my ninety-year-old grandmother closes her eyes in rapture and lets a flood of Pasolini poetry pour out in her native Italian, straight from her annals of her youth into today.

What’s so spectacular about committing a poem to memory is not that you can feel self-congratulory at 3am on a Wednesday (though that never hurts) but that you carry the poetry with you, so that it’s always at your fingertips when you are in need of it. And the reason it’s useful to have an internal storage device for poetry is that you may not know you are in dire need of it until that need is about to swallow you whole.

The first time I learned a poem by heart was in sixth grade, when everyone in my class was required to do so. A poetry novice, I asked my father for a suggestion and he was quick to direct me to Edgar Allan Poe.

“Annabel Lee,” he said, handing me a heavy tome of Poe’s Collected Works.

You’d be hard-pressed to find an easier poem to commit to memory. The rhymes leap off the page, hooking right into you like like those sticky burrs that fall off trees. With almost no effort, they adhere, apparently for good. Decades later, I can tell you Annabel Lee’s story from start: “It was many and many a year ago, in a kingdom by the sea” to end, “The wind came out of the cloud by night, chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.”

There was a lot of the poem I didn’t understand at the age of ten. What was a seraph? Or a highborn kinsman? But the wonderful thing about poetry is you don’t have to understand all of it — or even most of it. Particularly in the case of poems that rhyme, so much of the pleasure you feel in reciting them is letting the rhythms of the words roll over you. If you don’t believe me, stop what you are doing and say these words out loud:

“For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams/ Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes/ Of the beautiful Annabel Lee.”

It’s like a massage for your brain, from the inside out.

So I was delighted when my son graduated from pocket in his pocket to poem in his brain in fifth grade. His teacher said he could pick any poem he liked, and I advised him to choose one which rhymed, assuring him it would be permanently imprinted on his psyche for eternity.

“It’s the gift that keeps on giving,” I said, laying before him a selection of poems, Annabel Lee included. He made his choice wisely. Over the next few weeks, in the process of helping him learn the poem, I ended up memorizing it too.

“Whose woods these are,” he recited, standing in front of the classroom. “I think I know.”

I was in the back of the room, with the other parents, watching him recite it. He took his time, and it seemed to me that he was savoring the words as his lips formed them.

Fast forward six years, to the winter of 2021. It was in the middle of the second wave of Covid, before anyone was vaccinated, when my kids had been in online school for over a year with no end in sight. The Covid map tracking the spread of the disease across the nation had to invent a new shade of red, to distinguish “Very High” risk from “Severe.” For the first time in my life, we didn’t spend Thanksgiving or Christmas with my family, or my husband’s. Things were grim.

Desperate to escape the confines of our tiny apartment, we consulted that same Covid map to see where the virus appeared to be the most contained. Vermont, the map said. So that’s where we drove, after booking a few nights in a rustic AirBnB.

We’d been prepared for snow. Or, rather, we’d sought out the snow – it was part of the Vermont appeal. That didn’t mean we were prepared for it. It didn’t just cover everything, it buried everything. Who knew what was even hiding under the thick blanket of white?

It was a lovely sojourn, and restorative in more ways than one. Part of what felt so difficult about that winter was the lack of new-ness, how every day was always the same, looking at the same people, confined to the same rooms, the same sense of dread and tedium and frustration. But in this brave, new world, a land that more closely resembled Narnia than New York City, there were new sights and smells and feelings. There was wonderment.

One late afternoon, the day after a fresh snow, I was charged with walking the dog. I put a leash on him for fear he’d sink into a mountain of snow and never be found.We descended the icy stairs and walked down the utterly deserted road. To the left of me were trees. To the right of me were trees. Always everywhere, above, below, and on all sides, was snow.

I stopped walking and the dog stopped walking too. And what I heard then was something that was entirely new to me — total and complete silence. The wind wasn’t blowing. No creatures stirred in the trees. Nothing moved anywhere. The silence was immense. The stillness was staggering.

My pup, perplexed, or perhaps impatient, made the huffing puffing sound he does when he’s ready to move on. And the door that had been locked inside my brain blew open and out flew these words:

“He gives his harness bells a shake/ To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep/ Of easy wind and downy flake.”

The dog and I walked slowly down the road, marveling at the icicle-laden tree branches. Or, at least, I marveled. I can’t speak for the dog.

Out of my hidden poetry chamber, the words poured:

“The woods are lovely, dark and deep,/ And I have promises to keep.

And miles to go before I sleep./ Miles to go before I sleep.”

Who can say by what magic words renew us? I only know that they do — for me, at least. I know that when I learn the words by heart, they become a part of that organ, a part of the thing that beats in me, and keeps me walking, even in the darkest days of winter.