An interview with Jenny Jackson on the events that inspired her debut novel, Pineapple Street.

In the opening scene of Jenny Jackson’s hilarious debut novel, Pineapple Street, Sasha, cynically referred to by her in-laws as “Gold Digger”, is reluctantly rummaging through an unused bedroom in her four-story Brooklyn limestone. The bedroom houses an egg-shaped iMac desktop computer, a pipe buried in a drawer, and a ski jacket with a hoard of lift tickets latched to the zipper. The house serves as a portal to 1997. For Sasha, a graphic designer and Brooklyn transplant, returning to the 90s meant living in her rich husband’s childhood home, filled with his memories and family histories, and mostly, “his family’s shit”.

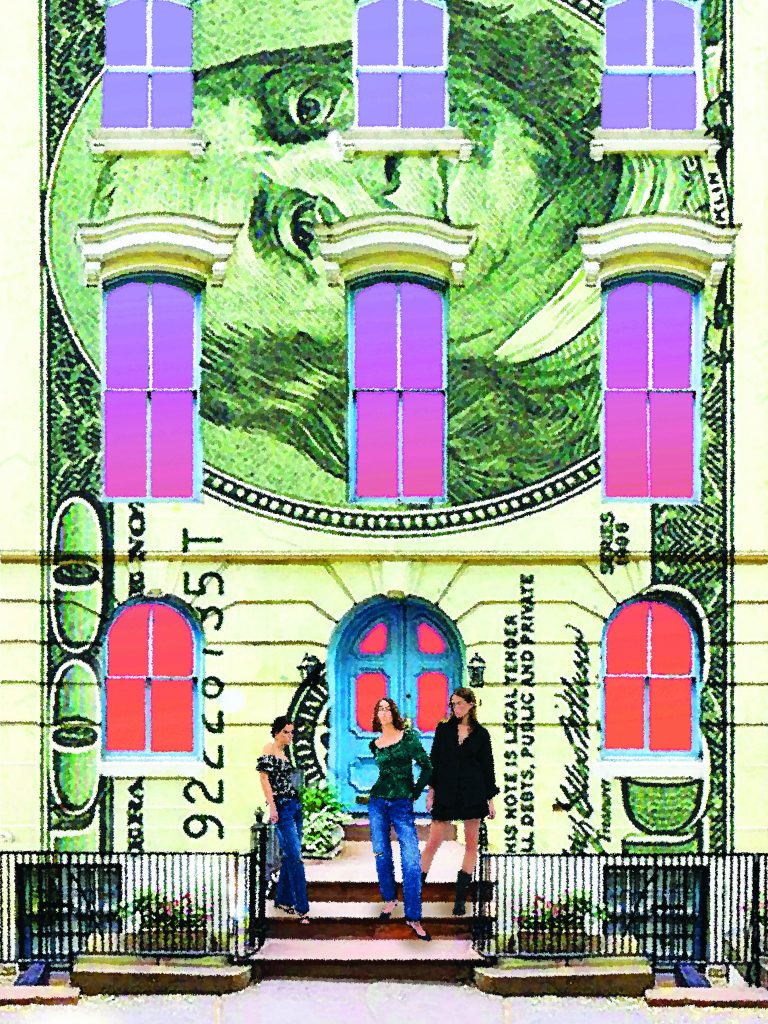

Pineapple Street tells the intergenerational story of the wealthy Stockton family through shifting points of view, as three sisters navigate the complexities of life, love, class, and privilege. The novel reads like a sociological survey of the one percent, giving its audience an inside look into the lives of Brooklyn’s elite. Jackson, a Vice President and Executive Editor, takes inspiration from the early days of the pandemic and her slice of Brooklyn Heights to chronicle the Stockton sisters’ eccentricities, competing interests, lessons learned, and above all, their loyalty that is bound by the ancestral limestone on Pineapple Street.

In a phone call, Jackson and I discussed the widening gap between racial and economic inequality, WASP family dynamics, the trust-fund anti-capitalist millennials who inspired Pineapple Street, and what MTV’s “Cribs” taught us about money. Our conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Pineapple Street is your first published book. Congratulations!

Thank you. I’ve worked in publishing for 20 years, but this is my first time sitting in the author’s seat.

Yes, I read that you are an Executive Editor and Vice President at Alfred A. Knopf. Have you written other books that have not been published?

I had not written any books before 2020. During the pandemic, I began writing something else as an exercise before writing Pineapple Street. It was an exercise in releasing demons and figuring out how to write a novel. Pineapple Street is my first complete book.

I always wonder if novelists have written books that have been shelved and if their debut novels are their first attempts at publishing. You began writing Pineapple Street during the pandemic?

Yes, I started writing it at the end of 2020. I was living in Brooklyn Heights on Pineapple Street and wasn’t leaving a 10-block radius. I missed my friends and was lonely; I walked around the neighborhood every day. I believe that the novel grew out of the experience of needing people to talk to.

It’s interesting that inventing characters and writing dialogue are derivatives of pandemic-caused loneliness. Was there an aha moment that led you to write a book set in Brooklyn Heights?

The novel is set in Brooklyn Heights because I felt so intensely connected to my tiny slice of Brooklyn at that moment. Three distinct lines of thought came together. I spent a lot of time with my family during the pandemic. I have two small children and we spent a lot of time with my parents and in-laws. A good friend of mine had the experience of living in her in-law’s beautiful brownstone while they were living elsewhere. She moved into her husband’s childhood home with their baby. It was strange because all his parents’ stuff was still there. She would tell me outrageous stories of living amongst their things. And then, simultaneously, on my wanderings, I became obsessed with this house on Pineapple Street. It was so big! No matter where you lived during the pandemic, your own four walls began to feel like they were closing in on you— but this house was enormous! It had huge windows showing a parlor with a chandelier and a grand piano. I fixated on who lived there. I mean, who has a grand piano in the city? Lastly, I was inspired by Zoë Beery’s article in The New York Times called, The Rich Kids Who Want to Tear Down Capitalism. She writes about socialist-minded millennial heirs who are set to inherit vast fortunes that are at odds with their morals. They want to give away their money and the family lawyers are trying to stop them. These three ideas spun around in my head. I would write, go for a run down by the Brooklyn waterfront, and then come home and pour these ideas into my computer.

Pineapple Street interlaces the lives of three sisters who are each navigating the flaws and insecurities that they believe are tied to generational wealth. In Sasha’s case— acquired wealth. Their recognitions of class and privilege are largely introspective and somewhat contradictive; they all seem to be searching for fulfillment, or, at the least, contentment. How did the characters develop?

Sasha, the in-law, came to me first. Her story is a natural place for the novel to open because she invites the reader into the rarified world of the Stockton family. She gives the reader an unvarnished look into how wildly strange the family is. I also knew I wanted to create a character who was around a decade younger than Sasha. I am a geriatric millennial, on the cusp of Gen X. My attitude as a young person was different from the Gen Z attitude about money. That’s where Georgiana’s story came from. She is delightfully bratty and, at the beginning of the novel, is very self-absorbed. I also knew that I wanted another point of view from someone inside the family who could contrast the attitudes of Georgiana and Sasha, so I wrote Darley’s character. She took a while to figure out. It wasn’t until I changed her name that her character started to flow.

I agree that Darley’s name is fitting. I enjoyed reading her corresponding chapters. She is outwardly poised and charismatic in her way— although we learn that her confidence is overshadowed by regret. Are there women in your life or events you experienced that helped shape Darley’s narrative and internal battles?

My best friend from college has children that are a full decade older than mine. She and I have had many interesting conversations about what that has meant for her life. She threw herself into motherhood while I threw myself into work. There were a lot of times when she grappled with trying to find meaning as her children grew older. She has done so beautifully but it was, in some ways, more complicated for her when she entered the workforce later. I was well-situated in my career before I had kids. Our conversations have informed the way I wrote Darley, who struggles with the same questions.

The novel captures the essence of millennial and Gen Z culture and the jarring differences between younger generations and older generations. Tilda’s character struck me. I am entertained by her brazen human qualities although they are out of touch with the cultural shifts— like economic and racial inequality— that her children are mindful of.

Yes, Tilda is the most extreme character. Her confidence is a combination of willful blindness and an attitude that if you wear a stiff upper lip, everything will be fine. Some of that is generational but her attitude toward her children is like her attitude toward money. She is willfully unexamined.

Right, and it’s clear to the reader that despite Tilda’s idiosyncrasies, her children rely on her.

I loved Tilda as a matriarch. Families that have a strong matriarch like Tilda or otherwise, have a fascinating way of orbiting around that person. She might not be the most emotionally in touch with her children, but she is the first-person Darley calls when she has the flu, and she’s the one Georgiana both relies on and blames for her problems.

The Stockton sisters internalize and excuse their race and class privilege. They intentionally practice wokeism in a way that is relatable to anyone who shares one or both characteristics. Have you had any of these moments yourself?

Yes. There are many things that were not examined 10 years ago that we would never do now, like Cinco de Mayo parties in college that were not thoughtful. Thank goodness we’re all waking up and taking a hard look at things we’ve done in the past that are harmful. A lot of people, regardless of background, have had to look at their baked-in racism and classism.

Georgiana seems to have the most poignant reckoning with her privilege. I adore the scene at the family dinner table where she retells a conversation that she had with Curtis at an Oligarch Chic-themed birthday party. Malcolm, the only person of color at the table, explains the nuances of perpetuating harmful stereotypes.

Yes, and she is aware enough to be mortified that Malcolm is the one to tell her.

Right, and she is aware enough to recognize that her family is not fully invested in the conversation anyway.

The scene gets recreated at the gender-reveal party for Sasha. Tilda regularly hosts theme parties that are full of stereotypes and microaggressions, and it would never strike her as inappropriate. Georgiana is the one to step forward and say “this is problematic” but she’s also wasted and emotionally out of control.

Earlier in the conversation, you said that the narrative for Pineapple Street was partly inspired by Zoë Beery’s article on the rich millennial heirs who are redistributing their wealth. The editorial foreshadows Georgiana’s character. You also said that you are a “geriatric” millennial.

How do the millennial and Gen Z attitudes towards wealth differ from that of older generations?

Growing up in the 80s and 90s, our attitudes about money were culturally shaped by shows like Troop Beverly Hills, Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, and MTV’s Cribs. We grew up thinking that money was awesome and if given our choice, we’d like to have a lot of it. It was a simple relationship between money and wealth that was unexamined. Over time, as income inequality has become greater, and the events of Occupy Wallstreet happened— and Bernie ran for office and AOC became a major player— our national attitudes towards wealth have shifted and young peoples’ attitudes towards inherited wealth have changed. I don’t think these young people have the same unexamined relationship with money. Gen Z is terrific. Their socially minded attitudes are going to help eliminate the huge income gap.

You begin the novel with a Truman Capote epigraph: “I live in Brooklyn. By Choice.” Where in the writing process did this quote come to you?

The quote came late. In the novel, Georgiana tells the story of the Truman Capote house on 70 Willow Street. In recent years the CEO of Rockstar Games bought the house and wanted to put in a pool. The neighborhood was outraged at the changes he wanted to make. It turns out that Truman Capote borrowed an apartment in the basement from a friend but never owned it. I lived in Manhattan when I was 22. I would hear people complain about the “B&T” people, meaning the “bridge and tunnel” people. There was this ridiculous snobbism about people who didn’t live in Manhattan. At the time, I would hear that and believe that living in Brooklyn was undesirable. It’s funny because the young people moving to NYC now all want to live in Brooklyn. It’s sought after, even prohibitively sought-after.

Jenny Jackson is a Vice President and Executive Editor at Alfred A. Knopf. Pineapple Street is her first novel.