Nicole Kear has been a beloved columnist with us at Park Slope Reader for more than a decade. Little did we know, though, that during these past twelve years she was hiding a big secret. Back when Kear was in college, she was diagnosed with a degenerative eye disease which doctors told her would eventually lead to blindness. Over the course of the next fifteen years Kear had kept this diagnosis a secret from everyone except for her immediate family.

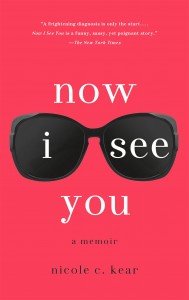

That all has changed, however, with the release of her debut memoir, Now I See You, a comedic, yet endearingly honest account of love, life, and starting a family before the lights go out.

We sat down with Kear to discuss her new book and “coming out” with her disease.

Park Slope Reader: When did you decide you were going to write this memoir?

Nicole C. Kear: Maybe five years ago I started working on a proposal for a different memoir—a mommy memoir, essentially like the stuff I wrote for Park Slope Reader—without the entire component of my eyes. I completely left it out of the 100-page proposal. My agent tried to sell it and unsurprisingly was not able to. After that didn’t work, I thought what can I add to this story to make it more compelling? It’s like when you’re watching a movie and are like, yea…duh!

PSR: Was it an active or unconscious decision to leave that out?

NK: It wasn’t active at all. It was a total default…like a crazy person.

PSR: As a writer, did you journal every day?

NK: No, I don’t even shower every day! The way that it came to be was my husband and I were going away for the night. Finally he was like, “Nicole, you can write about your eyes.” “Of course!” As soon as he said that I was like, what’s wrong with me?!

It’s funny thinking about that now. When I was in college and I got my diagnosis and still fresh, I took this seminar called 20th Century Feminist Spiritual Autobiography taught by a female rabbi and a nun and a minister. We read these amazing memoirs about women and had to write our own. I wrote this piece called “Star Light, Star Bright” and it is the college version of my book. But so that is kind of where it started…then I became crazy and didn’t tell anyone for fifteen years so it became something that wasn’t a possibility. So when my husband mentioned it, I thought, that is not only a great idea but the only idea.

PSR: That must have been terrifying though—this part of your life that you actively kept inside. How did you go back to your memoir and add that component?

NK: I didn’t go back. I started from scratch. It’s a completely different book. Even the characters are different. Because you know at first, it wasn’t really me. It didn’t have a huge life-determining factor to it. It was a completely different novel.

I started to write and it took me so long to write something decent. I had been writing for years and it had become so habitual to omit any reference to my vision loss.

So I was like, you know what? I’ll write a scene. I’ll tell the story of when my son was a baby and I was so tired that I tried to throw myself on the bed. I didn’t see it, and I fell onto the floor. So I wrote that scene and literally, I didn’t know how to write that and tell the truth of it. I was so used to telling people the fake version.

PSR: Was that an emotional experience for you?

NK: Yes. The good part about it was the humor. I was able to find the humor in almost all of it. It allowed me to feel comfortable doing it. It’s depressing! But because I gave myself permission to share the humor of it, that really tempered it for me. It was difficult, but it was also enjoyable.

PSR: That was such a big component of the book. It’s a heavy subject and a sad story. But you have this way of balancing it out and this ability to laugh at yourself. Was that something you always had with you growing up or did you develop that after your diagnosis as a way of coping?

NK: That’s just an innate thing with me. I’ve always had that temperament. As I grew older, it’s something that I strengthened and turned to. I’ve always been a person who likes to laugh, and frankly, make other people laugh. I genuinely do feel like an optimistic person. And it really does help just to laugh about it.

That was hard for me in writing about it, because there is a very fine line between being glib and humorous. I really feel like my book is a tragic comedy. It has both sides of the mask, and it is a delicate balance. The first iterations of the book were very funny—or pathetically trying too hard—but they were trying to be funny.

I would share my drafts with my friends and they would point out that I basically didn’t talk about my vision. I really didn’t want to discuss it! I thought it would be so heavy and depressing, so I put in as little of that as possible. My friends and my agent really had to press me. I was so scared of being too dark. Extracting the raw honesty of it was really challenging for me.

PSR: Why the ongoing secret throughout your life? Your career as an actress, as you explain in the book, prompted this decision. Why keep it going throughout your life after the fact?

NK: Really it was force of habit. In the beginning the reasoning was more that it was an irrelevant fact. In my early twenties it didn’t hamper me at all. I didn’t really need to tell people for any practical reasons…and then there were a lot of compelling reasons not to tell people because, as you say, I was an actress. It’s so hard to get work anyway you don’t want to give people extra reasons, especially when they’re not relevant!

But then they became more relevant. And I had become so accustomed to not telling people and compensating. And it’s hard—this is the thing that’s difficult about any progressive condition. It just keeps changing and it’s hard to keep changing along with it in response. Change is difficult. I was waiting for an obvious cut-off point, or a breaking point. But it was more of a series of small rock bottoms, not enough to actually trigger any change.

And once you don’t tell people something like that, it becomes very awkward! Imagine telling people “Oh I’ve known you for ten years and we’ve lived together, we’re roommates and I totally forgot to tell you this one thing!” So I didn’t do it. But now I had to do it. It’s been so weird, but really good.

As I anticipated, it’s an uncomfortable conversation to have…especially within the context of “I wrote this memoir!”

PSR: Now that your children are getting older, they must have known—it’s something that has been part of their existence. Did you think about them eventually spilling the beans?

NK: It’s true, it would have been untenable to keep this going. Kids are big blabbermouths. They were so young and they knew so little. I gave them little kid-sized morsels of information. Now they know more because they’re older, and it’s convenient because now everyone knows!

PSR: Was there any sense of betrayal from people that were close to you who didn’t know?

NK: There was no betrayal. People have been so understanding. Really. And I think because now they can read the whole book about why I didn’t tell them and read the whole back story. The best part about it is A. the release—that conversation’s over and I don’t have to dread it anymore—and B. it’s opened the door to new conversations and deepened friendships, as any act of honesty will.

Leave a Reply