As we board the subway, get in elevators, and jog down the sidewalks, we start to take for granted the feeling of pavement beneath our feet; it’s easy to forget that the structures around us have only been in place for about 300 years.

There’s a sense of comfort, after all, for us city dwellers—an assuring sense of groundedness and even permanence felt when making contact with New York’s foundation. We even allude to it in our daily conversations; we “pound the pavement” to find success, and “kick to the curb” things we want to discard. Is there anything in this world that invokes imagery of strength and efficiency like the concrete jungle?

If there’s ever a thing to snap one out of a state of urban sentimentalism it’s the foul stench that reeks from the waters of the Gowanus Canal. It’s an offensive reminder of the constant give and take between environment and urban development. In 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency declared the canal one of the nation’s most polluted bodies of water, adding it to the Superfund list to join the ranks of our country’s most hazardous waste sites. In December 2012, the EPA released a proposal detailing its plan to launch a ten-year, multi-million dollar cleanup of the canal.

I sit across the table from Beth Franz and Frieda Lim in Four and Twenty Blackbirds on Third Avenue, only 500 meters away from the canal. These two women are well acquainted with the dichotomy of New York’s green and grey worlds and have invested their careers in reconciling this divide. Franz is an associate at a landscape architecture firm and specializes in urban design and green infrastructure. Lim owns Slippery Slope Farm in Gowanus, and was part of the team who brought the Edible Community Garden to P.S. 39. Both have a thorough understanding of our urban ecosystem and are working to innovate the way we think about structure, its relationship to environment, and its potential pitfalls.

One of those pitfalls is storm water management. Over 300 years ago, long before the factories, subway lines, or sewers of modern-day Brooklyn, there was the Gowanus Creek and its network of tributaries. There were also trees, marshes, swamps, and fields that thrived off of rainfall, and animals that borrowed their own underground networks through the absorbent soil and loam that supported the world of surface dwellers. When heavy storms rained down, the water replenished the streams, and the excess sunk into the earth. The earth retained it for later, acting as a sort of sponge that could be squeezed for moisture in times of thirst.

This system was compromised when the Dutch began to settle and literally lay the foundation for what would become one of the largest cities in the world. The natural green spaces of Brooklyn diminished to a mere fraction of what they were 300 years ago, and factories, shipyards, paved roads, and warehouses took their place. With development came the removal of nature’s storm water management system and the installation of a manmade one. The newly industrialized Brooklyn of the 1800s needed land on which to build factories, and those factories needed a place to dump their waste. In 1848 the city approved the dredging of Gowanus Creek and the surrounding marshlands and began construction on the Gowanus Canal—one, big, open-air sewer.

We’ve come a long way since the days when it was acceptable to dump our waste straight into the canal, but what many may not realize is that this still happens, just less frequently.

We’ve come a long way since the days when it was acceptable to dump our waste straight into the canal, but what many may not realize is that this still happens, just less frequently.

The city uses a combined sewer system, which catches and transports both storm water runoff and raw sewage in the same pipes. Under normal conditions, it works fine. But when storms move in and produce an unusually high amount of rainfall, that’s when “shit happens.”

The overflow mechanism is triggered, and the spillover is flushed through combined sewer overflows (CSOs) straight into the nearest body of water. The spillover is more than just rainwater. It’s rainwater that has churned and mixed with everything we’ve all been dumping down the drain—soap, chemicals, cleaners, paint, oil, urine, feces, vomit—a slurry many living within the flood zones of Sandy dealt with firsthand. Specifically, there are ten CSOs that dump into the Gowanus, and OH-007 is the second most active.

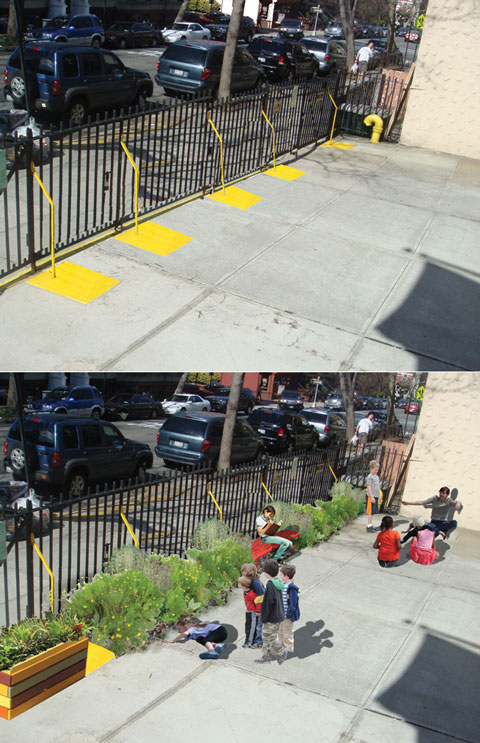

“It’s an enormous issue and huge environmental problem,” sighs Franz, “and what we want to do here in Park Slope will hopefully diminish our role in it.” Lim and Franz are heading up the Environmental Gardens & Education Committee, which has proposed a local public works venture called P.S. 39 Stormwater Garden Initiative Program. The initiative will repurpose space within the school grounds of P.S. 39, converting underutilized space into functional and beneficial solution to Park Slope’s storm water runoff. Specifically, the committee plans on introducing green infrastructure to the schoolyard and front garden areas by adding bioswales—small gardens that catch storm water—and by swapping out the current concrete walkway with permeable pavers.

The Committee recognizes that space in the schoolyard is a luxury and has taken that into consideration. Currently, the school’s perimeter fence is braced by metal structures that are not only a minor safety hazard for kids, but also eat up about a foot-and-a-half of space adjacent to the fence. The bioswales will fill that void along the school’s perimeter and serve as a sponge-like interceptor to puddles and torrents that gush through after heavy rains. The entrance of the school, which is currently paved with impenetrable slabs, will be resurfaced with permeable pavers with spacers that are more conducive to groundwater absorption. Layers of gravel, sand, and mesh will protect the spaces so weeds won’t be able to grow in between.

It doesn’t sound all that complicated because it isn’t. In total, the project is only estimated to cost about $125 thousand and can be implemented over the course of a couple months. “Once installed, [the improvements] will be self-sustaining, requiring little maintenance and no additional manpower,” explains Franz. “All of the plants will be native varieties and will be able to live entirely off of natural rainfall.”

The impact of these changes, however, would be meaningful. For one, the storm water runoff from P.S. 39 drains directly into OH-007, that second most offending outfall site. While it’s tricky to guess exactly how much of that runoff will be reduced, Franz and Lim expect the new green infrastructure will divert a significant amount of storm water away from the outfall.

Lim looks at the table behind us where her daughter and niece giggle and play. It’s clear that P.S. 39 was a strategically chosen as the site for this project for reasons other than its proximity to OH-007.

“We’re hoping this project will be a lesson for the kids that they can take home and pass along,” say Lim. “It’s important to us that this be used as an educational tool. We want people to take an interest in what this all is and see how it’s done.”

One of the main tenants of the plan addresses a current lack of sustainability education in our schools’ curriculums, as explained by Karen Herskowitz, P.S. 39’s parent coordinator: “Students at P.S. 39 are part of a future generation that will be faced with many environmental challenges. Our children will be tasked with making innovative changes in the way our population lives or face dire consequences.” If implemented, the project will be the first of its kind, and both Franz and Lim are excited about the prospect of Park Slope leading the way for future green infrastructure improvements throughout the city.

The P.S. 39 Stormwater Garden Initiative program was one of twenty other proposals competing for a piece of Representative Brad Lander’s $1 million Participatory Budget, which went to ballot on April 7. Frieda, Lim, and the rest of the committee had hoped to win a favorable vote, but unfortunately, their project did not make the cut. While they are disappointed with the outcome, the Committee will continue to seek out alternative sources of financial support for their plan.

To learn more about the project and ways to get involved, visit the P.S. 39 Park Slope Stormwater Garden Initiative’s Facebook Page.