“Here’s the first of many flyers you’ll get tonight,” smiles a bookish white man, extending a sheet of paper as I approach Congregation Beth Elohim’s Temple House, located across the street from their majestic but under-repair sanctuary in Park Slope. It’s a humid, mid-September evening, and, as I pass through the open doors, an older woman hands me another page. “Unrelated,” she explains.

A Progressive Movement Grows Strong in Brooklyn

In the time it takes to climb the stairs and claim a folding chair in the steadily filling ballroom, I have, indeed, run a gauntlet of progressive politics. I now have flyers for organizations that fight voter suppression and are working to end solitary confinement; reminders to bring my own bag to the grocery store and get involved with participatory budgeting; invitations to an Indigenous People’s Day Celebration and town hall meetings on climate change and the NYS Constitutional Convention. I’ve signed letters to Governor Cuomo and Senators Gillibrand and Schumer urging them to defend the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. “This letter is different. It’s for the carbon-tax,” encourages a casually dressed white-haired woman as she approaches my seat with a clipboard and pen.

In the front of the room, a slideshow asks in black and white: “Race: does it affect where you choose to live? To eat? To socialize? To send your children to school?” Above the din of warm greetings and exchanged hugs floats the accompaniment to the projections, a recording of the rally cry, “Whose streets? Our streets!”

It’s hard to find a simple way to encapsulate the multifaceted, nonhierarchical, community-based resistance movement that is #GetOrganizedBK (sometime hashtag-less, sometimes abbreviated as #GOBK). “It doesn’t exist in any typical structure you can think of,” Rabbi Rachel Timoner tells me, as she, New York City Councilmember Brad Lander, and I huddle, post-meeting, in a ballroom-adjacent children’s playroom piled high with playmats and primary-colored toys. Formation? Gathering space? The two debate. “It’s a set of people who want to do this work together and want to get better at doing it together,” says Lander. “And that is powerful.”

Timoner, Senior Rabbi of Congregation Beth Elohim since 2015, and Lander, Mayor DeBlasio’s successor as representative of Brooklyn’s 39th District, are well-connected and trusted local leaders with decades of collective experience in community organization. In the immediate wake of Donald Trump’s election, as people reached out to them in confusion, anger, and fear, they met at Dizzy’s, put their heads together, and set a date to take action. Tuesday, November 15, exactly one week after the election, #GetOrganizedBK met for the first time in CBE’s sanctuary. The first meeting, which drew close to 1,000 attendees, offered a collective space to grieve, but also spurred those congregated to ask, as Timoner recalls, “In what ways do we think people are going to be impacted, and how do we think we can start to defend people and protect civil liberties.”

Early meetings set a template moving forward; notable speakers and panelists, often from city-based nonprofits, discuss salient topics. Afterwards, breakout groups gather in classrooms, nooks, playrooms and basements to delve deeper into specific issues. In the year since the election, Get Organized Brooklyn has mobilized en masse many times, including rallies in opposition to Trump’s travel ban and a “die-in” in opposition to the proposed Obamacare repeal, but the bulk of the work — letters written, phone calls and donations made, events organized — is done by these issue oriented working groups. Arts as Activism, Combatting Antisemitism & Islamophobia, Free Press, Women’s Health, Solidarity With Immigrant Neighbors, and at least eight other subgroups form the backbone of #GOBK and carry the torch of activism from day to day and week to week in coffee shops, bars, and living rooms.

And that was really the point all along. As Lander puts it, they wanted to “just provide some room for people to self-organize and get started doing things.” “One of the key parts of the model,” Timoner adds, “is that we realized pretty early on that we’ve just gotta get out of the way. There are so many people and so much energy and so many issues that if we try to control it or direct it, we’ll just slow it down.”

Timoner also expresses amazement at how the working groups have blossomed. “There are often so many efforts within Get Organized Brooklyn,” she says, “that we can’t even keep track of all of them. We’ve often been surprised — we’ll see something fully formed out in the world and say, oh, that came out of this?! And we didn’t even realize. It’s very cool.”

The evening’s meeting, “After Charlottesville, what must we do?” was orchestrated by #GetOrganizedBK’s Racial Justice working group almost exactly a month after a white-nationalist rally resulted in the murder of counter-protester Heather Heyer. In the time since, Trump cancelled DACA, a program which aided 800,000 immigrants. Then came hurricane Harvey. And hurricane Irma. “We’re not, as human beings, built for this level of chaos,” Lander remarks. “A peculiar feature of these times is not just that there’s hate, but that it’s chaos in our minds.” The benefit, then, of the working group structure, is that people can lovingly tend their own patch of grassroots.

Wendy Viola joined Indivisible BK, a working group connected to Indivisible groups nationwide, after the first #GOBK meeting. “I really appreciated the concreteness and discreteness of the actions and goals,” she shares. The group meets every other week to work on “keeping folks engaged and taking manageable actions to keep the pressure on our elected officials,” but they also collaborate with other working groups. “#GetOrganizedBK put me in much closer and more frequent contact with the people in my neighborhood, which I’m very grateful for.”

The night’s meeting doesn’t start on time, but by the time things kick off, the 300-seat space is filled to capacity. The vast majority of the audience is white and over 50, but there is a self-awareness to the homogeneity. They are there to learn and fortify one another for the fight ahead. “When you see people up there who are working on these different efforts and campaigns with such clarity and intention and great analysis and dedication, it’s so hopeful,” says Timoner. “And when you see the room full, it’s so hopeful.”

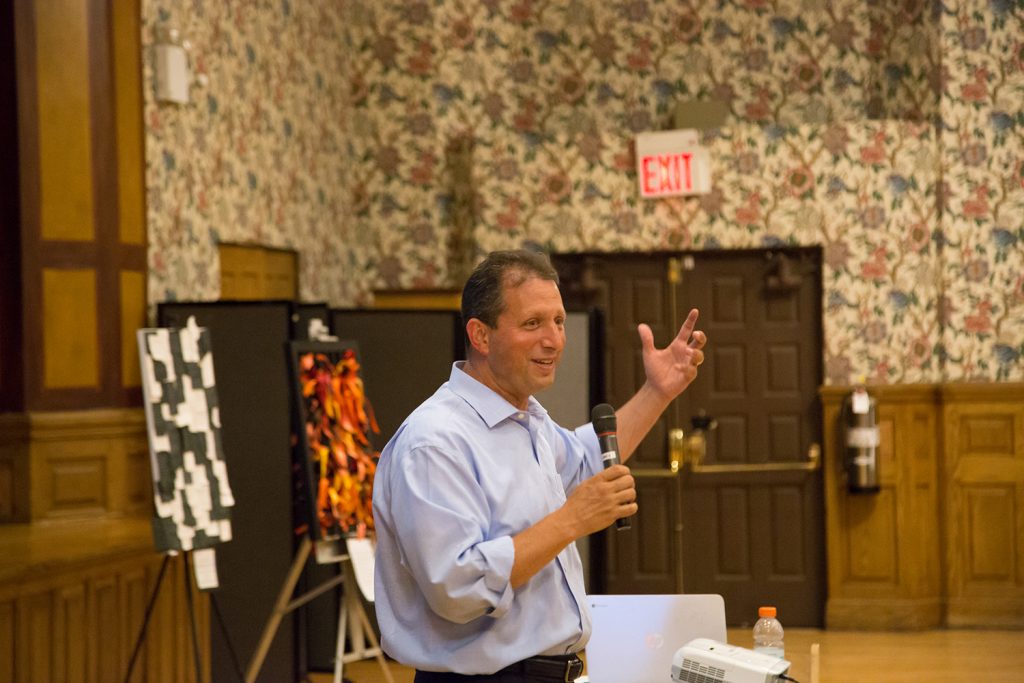

After introductory remarks by Timoner, Lander, and the co-leaders of the Racial Justice group, Eric Ward, the Executive Director of the Western States Center, gets up to speak. In a little under 15 minutes, he outlines a history of white supremacy in America. “The best defense,” he concludes, “is visible, unapologetic unity.” Later, Timoner echoes the sentiment. “I 100 percent believe what he says. What we can actually do is convene around our shared vision of democracy. When we do that, that is not only our best defense, but also moves us toward the city and country we dream of.”